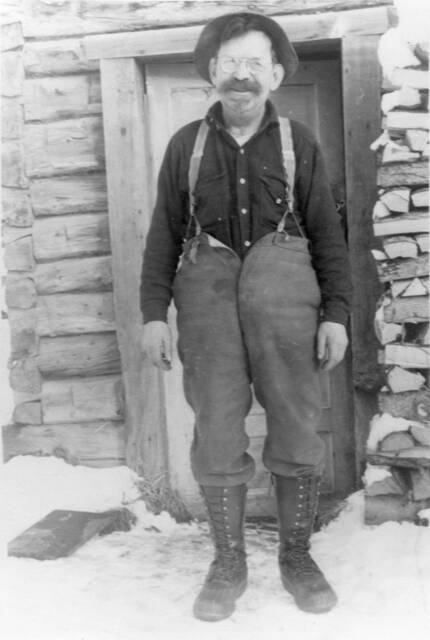

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Former longtime Kenai resident Charles Wagner was a memorable character. After living for about a decade in Seward, he purchased a residence on the lower Kenai River and remained in the area for 30 years. In Part One, readers learned about Wagner’s fragmentary early history and his penchant for stretching the truth in the name of entertainment.

By most accounts, Charles “Windy” Wagner was an energetic, boisterous storyteller who entertained his listeners, even some of the ones who rolled their eyes and knew he was full of hot air.

Hunter John P. Holman fondly recalled meeting Wagner in a cabin up the railroad tracks from Seward in 1917. Inside, Wagner was standing over a woodstove, merrily cooking breakfast for two other guests, and he insisted that Holman join them. Wagner, he said, whipped up “a great stack of hot cakes” along with fried eggs and bacon, cornmeal mush and coffee.

“All the while,” Holman reported, “Windy talked and laughed and made us feel as though he was having the greatest time of his life in cooking for us.”

Wagner evidently liked to cook for guests. Joe Ross, in “Once upon the Kenai,” also remembered being the beneficiary of Wagner’s generosity: “What a character! He could tell stories, and very good ones, all night and day. One of our duck-hunting trips ended at Windy’s log house. He cooked us a very good meal, and I spent the night listening to many of his fabulous tales.”

Wagner’s repertoire also included practical jokes and tall tales. Homesteader Rusty Lancashire recalled the time in 1948 when Windy, an adroit, productive gardener, told her husband Larry that a man had stopped by and asked to buy a hundred pounds of cabbage from him. Wagner told the visitor that he “couldn’t sell any to him as he didn’t want to cut a cabbage in two.”

Another time, said Lancashire, Wagner noticed the local U.S. commissioner, his wife and another woman approaching while he was cooking beans. He decided to add baking powder to the beans and then fed them to his guests, who “left almost as soon as they finished their lunch…. Baking powder makes beans almost explode before you eat them.”

In early March 1916, friend and fellow trapper Charles Coach reported to the Seward Gateway newspaper that Wagner had narrowly escaped serious injury a few days earlier, despite an unusual and potentially dangerous accident. Wagner, said Coach, had fallen 15 feet from a tree limb after cutting it out from beneath himself “in a state of absent mindedness.”

Coach claimed to have witnessed the incident, which involved Wagner climbing the tree to prune back some branches growing too close to his stovepipe. After sitting on one stout limb and trimming several others, he then blithely sawed through his own perch.

Coming to Kenai

In his early forties, Charles Wagner was described as short, with a medium build, brown hair and blue eyes. At his death 40 years later, he was 5-foot-3 and weighed only 123 pounds. Despite his small stature, he was known for an outsized and energetic personality.

He guided big-game hunters for at least a decade. During the 1910s, he trapped in the Skilak Lake area, mostly with partners Frank Standifer and R.N. McFadden. He may also have trapped with John Peter “Russian Pete” Kalning at this time, although he definitely paired up with Kalning in the 1920s.

During the winter of 1912-13, Wagner, Standifer and McFadden earned an estimated $2,000 for their trapping efforts — equivalent to the purchasing power of more than $60,000 today.

After spending several autumns as a licensed hunting guide and several winters as a trapper, often stationed out of Seward, Wagner moved to the western side of the Kenai Peninsula. Although his pursuits changed very little, he seemed to settle in there.

On Oct. 11, 1920, Wagner became a homeowner.

A bill of sale, bearing this date and beneath a letterhead for Dawson & Berg General Merchandise (Kenai), stated: “This is to certify that I, the under signed hav sold and bill, of saled to Charles Wagner one log house in the village of Kenai this is known as the Coal Tar Johnson house, Price being Two Hundred Dollars $200/00 for which I have received payment. Signed Emil Ness. Witnesses Emil Berg and W.N. Dawson.”

The identity of “Coal Tar” Johnson is unknown, as is the reason that Ness was selling Johnson’s cabin, which stood about 6 miles upstream from the mouth of the Kenai River.

Sometime during the next two decades, Wagner staked out 42.88 acres of land around his cabin, and in 1944 he applied for a homesteading patent on his parcel. His witnesses were Paul Shadura Jr. and Herman Hermansen. Five years later, on April 13, 1949, his patent was granted.

During much of the 1920s, Wagner trapped in the Tustumena Lake area and in the lake country north and east of Kenai. He also joined the crowd of other trappers who spent summers in Kenai working in the commercial-fishing business.

Dena’ina elder Peter Kalifornsky recalled Wagner being one of the men who trapped on Bear and Indian creeks, which flow into Tustumena Lake. Prior to the 1930s, Wagner appears to have stopped spending winters at Tustumena — Andrew Berg’s last journal entry about him occurs in 1928 — and started doing more of his trapping closer to home.

When Robert Huttle spent the winter of 1933-34 on Tustumena Lake, Wagner was no longer around, but his presence could still be felt. In his daily diary, Huttle referred to a trapping shelter near the mouth of Bear Creek (now Moose Creek) as “Windy’s cabin,” which was then being used by Pete Kalning and John “Frenchy” Cannon.

A 1972 Kenai National Moose Range report refers to a then-recently burned Canoe Lake trapper’s cabin that had been built in about 1938 by Windy Wagner and Harry Mann, both of Kenai.

As the 1920s came to an end, Wagner, who had been considered a “former licensed guide” since at least 1923, became a foreman for a bridge-building project downstream from Cooper Landing.

The first bridge to span the Kenai River was constructed in 1920 just upstream from Schooner Bend, but that bridge soon began to suffer the effects of bank erosion. The Alaska Road Commission then contracted with a Washington-based builder in 1929 to erect a new, covered bridge right on the tight meander that forms Schooner Bend itself.

When a census taker came through the area in October 1929, Wagner was 52 years old and the head of a household containing five other men also employed on the project.

But not all of his productivity was positive. The late 1920s also marked the beginning of a rise in Windy Wagner’s troubles with the law.