AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is Part Two of a two-part story about a few of the unlucky and the unwise among the long history of medical professionals in Seward. In Part One, Seward chiropractor O.L. Albery and his companion, Alfred Thibbert, embarked on a hunting trip to Montague Island, arriving on the island’s west coast Dec. 2. After stashing most of their food supply near their landing site, they hiked overland to the east coast where they found themselves trapped by severe weather.

Reports varied, but it is safe to say that, on Nov. 29, 1941, when 49-year-old Dr. O.L. Albery stepped onto the Seward mail boat that would take him and Alfred Thibbert to Montague Island, he stood about 5-foot-8 and weighed approximately 200 pounds, comfortable in middle age.

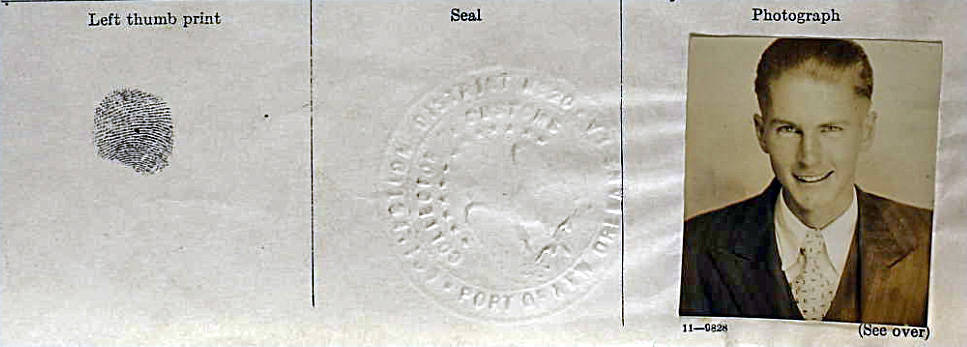

The 29-year-old Thibbert, on the other hand, was rail thin. According to the draft registration card he had signed in January, he stood 5-foot-11 but weighed only 133 pounds — just 8 pounds more than he’d weighed a decade earlier when he had applied for a Seaman’s Protection Certificate.

These physiological differences would prove critical as they attempted to wait out the fierce winter storms keeping them on the island’s east coast while their main food supply lay cached on the west coast, beyond the snowy spine of mountains running the 50-mile length of the island.

According to an article later in the Anchorage Daily Times, the weather in the region had been bad on the day they arrived on Montague Island — about 20 degrees Fahrenheit, with strong northerly winds. The mail boat that delivered them to McLeod Bay had struggled through a midnight storm on its approach to the island.

But the weather worsened considerably after the two men hiked to the eastern coast. They were pounded by a storm and struggled to reach the Nellie Martin River in Patton Bay.

Once there, as they sheltered in a rough-hewn, abandoned cabin, they found themselves trapped by ice and wind-blown snow.

And it was at this time that they learned their ammunition, drenched and corroded by the storm on the gulf, could not be fired. Thus, rather than hunt, they were forced to scavenge for their meals.

One report said the men subsisted primarily on mussels and other shellfish. Although these food sources, when they could get them, contained protein, they offered little fat and few calories for the effort required.

The Seward News reported that the men also combed the beaches for dead birds and gathered up whatever they could find living in decayed wood or other sources. The pickings that winter were decidedly slim.

They waited for help to arrive, but December concluded without a rescue, as did January.

On Feb. 5, 1942, an article entitled “Help Needed in Search for 2 Men of Seward” appeared on page one of the Anchorage Daily Times. Frightened by her husband’s prolonged absence, Janette Albery, wife of the chiropractor, had raised the alarm and managed to get the attention of the head of the Alaska Defense Command, Major Gen. Simon B. Buckner, Jr., who had ordered an Army plane to fly over the island and look for the two hunters.

An Air Corps pilot reported no sighting on his first flyover, so he made another in the hope that the men, perhaps hearing the plane the first time, might light a signal fire to attract his attention on a second go-round. But his second pass was as unrewarding as the first.

On Feb. 19, a Navy patrol plane passed the east coast of the island and reported seeing two men at the mouth of the Nellie Martin River. Both men, the pilot said, appeared to be waving frantically. A second plane was dispatched to drop provisions, by parachute, down to the two men.

Soon, a rescue vessel, the Siren, manned by civilian volunteers from Seward and Valdez and equipped with Army supplies, set out for the island.

Mel Horner, who had lived in Seward since 1908, was part of the rescue party and, in the third volume of Mary J. Barry’s history of Seward, offered these observations:

“When we got to the island (on Feb. 25), a storm was raging and it was a long time before we could make it to the beach. There we found the doctor by a rude shelter, and lying under a blanket was Thibbert, dead from starvation…. (Early in their ordeal), they hoped that a plane flying over might happen to see them, or that searching expeditions would be sent out if they did not turn up, but they saw nothing for weeks.

“Then, one day a plane flew over. The men shouted and waved their hands in hopes that the aviator would notice, and felt sure that help would soon be on the way. The doctor tried to be as optimistic as possible … but Thibbert gave up hope when no airplane ever returned that way…. After the disappointment of being overlooked by the plane, the young man soon succumbed, not having any hope left nor desire to live.”

Dr. Albery, a bearded shadow of himself at about 90 pounds, was so emaciated that his rescuers, some of whom knew him personally, failed at first to recognize him. He told the rescue party that he had seen the food-drop made days earlier but had been unable to locate it.

He also said that Thibbert had died in early February, perhaps shortly after the Army flyover. At one point, he said, he himself had gone 37 days with almost no food in order that anything edible they found might help Thibbert. The young man died in Albery’s arms as he attempted to feed him spoonfuls of warm mussel broth.

When the Navy patrol plane had gone by and spotted two men at the river mouth, only Albery had still been alive. He said he had been propping up Thibbert’s body to emphasize the seriousness of the situation.

Albery and the body of Thibbert were taken to Seward — Albery to his home in the care of his wife, the body to the local mortuary.

From his rescuers, the chiropractor was shocked to learn that the United States had been at war for more than two months.

The news of the rescue appeared in papers all across the country. When the story ran in The Columbus (Nebraska) Telegram on Feb. 28, it appeared alongside a war story entitled “U.S. Inflicts Heavy Losses on Jap Navy.”

Over the succeeding weeks, the chiropractor began to bounce back. When he filled out his draft registration card in May, for instance, Albery was listed again at a robust 200 pounds and was working anew in his Seward chiropractic business. But a continuation of the good life was not in his cards.

Before the year ended, Dr. Albery, his wife and their three children packed up and left Alaska. They spent time in both Oregon and Washington, but it while they were living in Gold Bar, Washington, in September 1951 that Dr. Albery learned that a warrant had been issued for his arrest.

He was apprehended and charged with manslaughter in connection with the May 14 death of a 20-year-old, diabetic Oregon woman he had been treating for more than two months. According to relatives of the dead woman, Albery had withheld insulin from the patient and advised her to ignore her previous doctors’ dietary advice and to eat whatever she wanted, including sugars. She lapsed into a coma and died in a hospital 16 hours later.

Albery had also been practicing his profession in Washington without a license.

In May 1953, he pleaded guilty to the manslaughter charges and was sentenced to a maximum of 20 years in the Washington state penitentiary — with the full sentence suspended because of Albery’s own poor health. Details of his physical condition were not disclosed, but he got off with three years of probation, a $200 fine and a ban on working as a chiropractor.

In 1956, his 16-year-old daughter Shirley died.

Dr. Albery himself passed away four years later. He was 67 years old.