By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

Author’s note: A much shorter version of this story first appeared in the Redoubt Reporter in January 2009. More information has come to light since then.

Near the end of Tony Bordenelli’s attempt at the record, his badly blistered left hand was sporting a rubber glove, and his right thumb was wound with wrinkled medical tape. He staggered from lane to lane in Soldotna’s new bowling alley, the Sky Bowl, sending one ball after another toward the pins at the other end of the hardwood.

Doggedly he persisted until, at 3:19 a.m. on June 26, 1960, he completed his 1,002nd consecutive game, breaking the world record of 1,001 straight games set by Plainville, Connecticut’s 37-year-old Steve Karpinski, who had completed the task in 110 hours and 7 minutes.

At that point, according to a July 8, 1960, article in The Cheechako News, Bordenelli’s wife, Eyvohn, gave him a celebratory hug and a kiss, which prompted the 45-year-old, 147-pound Bordenelli to pick up his bride and swing her around in his arms.

Then someone in the crowd of spectators called out, “Are you through?” And Bordenelli, rarely one to evade even the perception of dodging a challenge, replied, “Well, I think I’ll just bowl six more games and give that fool in Connecticut something to shoot at.”

Bordenelli had bowled a 106 in game number 1,002. In the next six games, he went on to post a 112, a 107, a 115, a 104, a 133, and a 116, mostly to the cheering of spectators marveling at his endurance.

In the end, he had bowled 1,008 straight games in 79 hours and 45 minutes, averaging 101.7 pins per game and nearly 13 games an hour. By the estimate of Sky Bowl owner Burton Carver, the right-handed Bordenelli had bowled about 40 percent of his games left-handed, including his low-score game (his 880th) of 13. His highest score for one game had been a 183.

A team of eight scorekeepers had worked in shifts to keep track of Bordenelli’s progress and to form an official record of the event. After all the numbers were tallied, they determined that Bordenelli had made 924 strikes and had knocked down a total of 102,548 pins.

Alan Phillips, who had been a 15-year-old scorekeeper during some of the evening and early-morning hours, said that the attempt at the record “was the most exciting thing going on in the whole town.” Soldotna at that time had fewer than 500 residents and was still four years away from incorporation.

“Back in those days, the bowling alley was one of the only gathering places, other than the post office,” Philips said, and so local residents wandered in and out during all times of the day to check on Bordenelli’s progress.

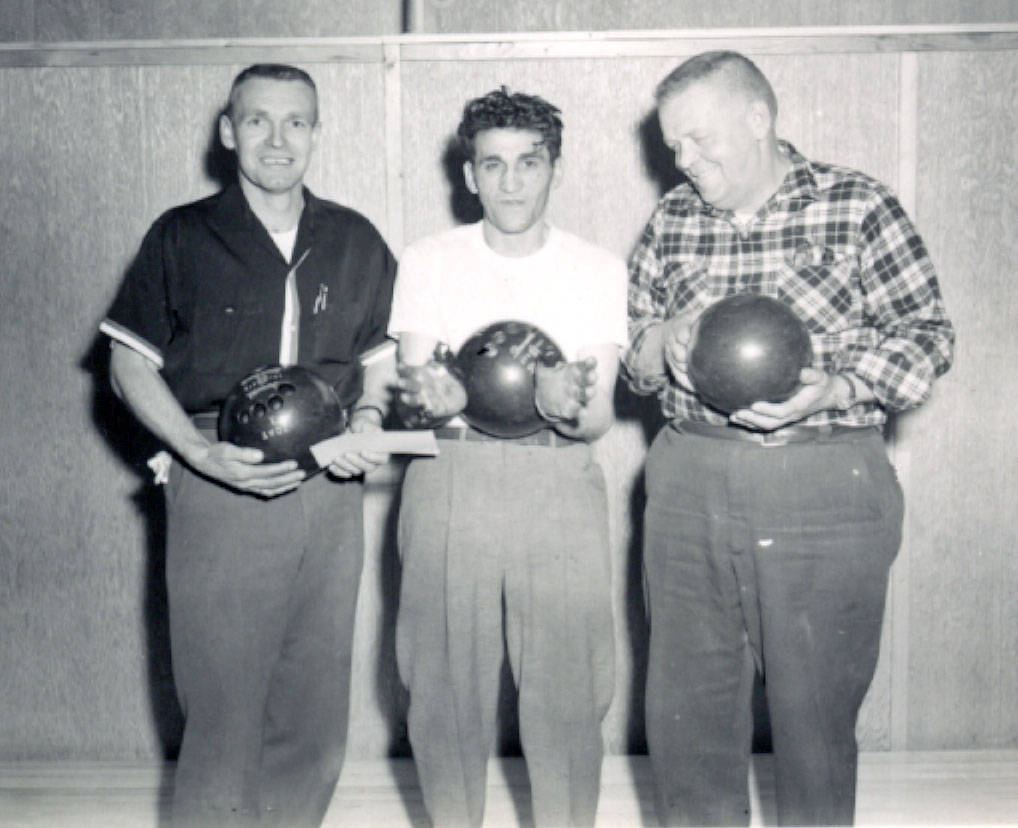

After the final game, Bordenelli posed for a photograph with Carver and with his trainer, Charlie Hill, who then gave the exhausted bowler a rub-down for his aching muscles. In the victory photo — which appeared on page one of the newspaper under a banner-headline proclaiming his success — all three men are holding bowling balls, but Bordenelli is holding his ball with his wrists instead of his gnarled hands. Blood can be seen on his right hand, while both of his thumbs are coiled in tape.

According to Bordenelli’s good friend, Ray LaFrenere, who wrote about the incident in the history anthology “Once Upon the Kenai,” the whole affair came about because of Bordenelli’s affinity for gambling — a predilection also remembered by other area residents of that time. LaFrenere said that if his friend had been alive in the days of Skagway’s famous Soapy Smith, “I’d guess that Smith would have had to take a back seat.”

LaFrenere claimed that Bordenelli, who hailed from Colorado Springs, Colorado, and owned the Jet Bar in Kenai, “bet a couple high rollers that he could bowl 1,000 games nonstop.” That bet apparently led Bordenelli to Carver, who helped him set up the event.

They began by contacting the American Bowling Congress to find out information concerning the feat, and that is when they learned of Karpinski’s mark. The Sky Bowl sponsored Bordenelli, and Carver promised him a check for $1,000 if he succeeded in breaking the record. Carver also encouraged spectators to contribute to the pot, and Bordenelli said he would give all the money to charity if he failed.

The Brunswick bowling company furnished Bordenelli with three specially fitted balls since he planned to bowl on three lanes simultaneously. He was allowed to break for 15 minutes each hour, but was not allowed to save his breaks and use them cumulatively. Plans were made to have a physician standing by in the latter stages of the attempt — just in case.

On Day Two, when a bloody callous had developed on the thumb of Bordenelli’s left hand, Dr. Paul Isaak arrived to remove the callous, tape the thumb, and cover the digit with a protective metal guard.

Painful hands and fingers were not the first major hurdle that Bordenelli encountered, however, according to the newspaper. The Cheechako reported that the bowler’s biggest problem early on was his desire to sleep. Once he overcame that, the paper said, he stayed on pace for the record.

A challenger appears

But where Tony Bordenelli is concerned, there is usually more to the story.

Almost three years later, a Kenai Peninsula bowler set a world mark in endurance bowling. In the April 26, 1963, issue of The Cheechako News appeared this headline: “World Marathon Bowling Record Set by Kenai Man, Beats Bordenelli’s Time.” Thirty-five-year-old Bill Kummert — who was married to Eadie, proprietess of the Last Frontier Bar in North Kenai — broke the record in the Kenai Bowl by completing 1,009 games, one more than Bordenelli.

Between 8 a.m. on May 30 and 7:12 p.m. on June 2, Kummert bowled for 71 hours, 15 minutes. He averaged 92.8 pins per game and 14 games per hour and racked up 912 total strikes.

“Bowling fans crowded the Trophy Room of the Kenai Bowl to cheer on the contender as he continued to roll game after game without sleep or rest,” wrote the newspaper. “Mrs. Kummert was present to lend encouragement and in final games helped direct Bill’s play when exhaustion began to take its toll.”

Although Kummert claimed in the end he felt “fit as a fiddle,” he was hardly unscathed. He was limping and had blistered feet. He had also pulled a tendon in his left ankle and another tendon in his right ring finger, and at one point he had reacted with a dazed grogginess after taking pills to help him stay awake. Despite alternating between nylon and leather gloves to keep his hands intact, by the end he was resorting to palming the bowling balls and throwing them rather than rolling them down the lanes.

Like Bordenelli, Kummert was allowed 15 minutes of rest per hour. Unlike Bordenelli, he took one longer break — five hours on the evening of June 1 — although he did remain in the bowling alley.

Of course, Bordenelli, who was in attendance during much of the final stretch, seized on Kummert’s big break as a reason to discount Kummert’s record and count his own as still intact. In a letter to the editor, dated June 7, Bordenelli wrote, “The true facts of the Marathon Bowling. I, Tony Bordenelli, claim that Bill Kummert did not break my World Marathon Bowling [record].”

Bordenelli said that the hourly 15-minute breaks were designed to be taken only if desired but could not be saved and used as one larger break later on. Therefore, he contended, Kummert broke the rules when he took five hours off. He did concede that Kummert had bowled one more game than he had and in a shorter period of time, but he asserted that Kummert’s shot at the record had to be disqualified.

“Tommy Thompson, who is manager of the Kenai Bowl, told me he picked up all score sheets [on Saturday night] and thought that the marathon was over,” Bordenelli wrote. “So, as far as I am concerned, it was over…. I feel that anyone that breaks my record will have to break it under the same conditions that I and the rest of the marathon bowlers had, continuously bowling with the 15-minute breaks if wanted.”

2nd claim to fame

Even that letter, though, was not the last time Tony Bordenelli would appear in print and astonish some readers.

In his later years, Bordenelli moved to Anchorage, where at the age of 89 he once again made headlines by demonstrating his toughness. In a 2003 article in the Anchorage Daily News is a report of Bordenelli trying to fight off an intruder in his Fairview neighborhood home. Accompanying the story is a color photograph that shows Bordenelli with a small cut on his left temple and with a swirl of yellow and dark purple around his left eye.

According to the story, on the evening of June 16 he and his second wife, Patty, and their infant daughter were at home when a man burst in through the front door they had propped open to help circulate the air inside. While his wife and child hid in a closet, Bordenelli faced the intruder.

The attacker, wielding a pellet gun, shoved Bordenelli into a bathroom and onto the floor, where he straddled the elderly man, demanding money. Bordenelli kicked the man between the legs.

“That’s when he shot me,” Bordenelli told the paper, showing a reporter a bandage on his upper chest. And when Bordenelli tried to rise, the attacker pistol-whipped him across the left temple before stealing money and other items from his pants pockets and fleeing the scene.

The reporter, in recounting the incident, called Bordenelli “a former boxer” and referred to a newspaper clipping of his bowling record framed on one wall.

Bordenelli, for his part, remained tough and resolute, even in defeat. “If I saw him coming in,” he said of the intruder, “it would have been a different story.”