Over the past 50 years or more, the City of Kenai has attempted on several occasions to capitalize on its long history, particularly on the remnants of the past still evident at this gathering place near the mouth of the Kenai River.

Even today, the city’s website features a section called “Old Town,” which asks visitors to “consider a walking tour,” starting with obtaining from the Kenai Chamber of Commerce’s Visitors & Cultural Center a map containing highlights and suggested sites, such as Fort Kenay, a collection of historic cabins, the Russian Orthodox Church, and so on.

No longer on the city’s online list but still fronted with a small historic marker is a group of mostly white-painted Kenai Natives Association buildings in the 500-block north-northwest of Overland Avenue. More than a century ago, this site was home to a portion of the federal government’s agricultural experiment station.

The Kenai Station, which had moved from a crop-oriented to a dairy-and-beef-centered facility during its decade of existence, closed in 1908, as officials determined that Kenai’s chilly climate and, at that time, inaccessibility made it difficult to sustain agricultural production.

Afterwards, Prof. Charles Christian Georgeson, the man in charge of all agricultural experiment stations in Alaska, claimed the closure was temporary and sought tenants for the farm and its buildings, always with the caveat that he might need the place again one day.

But, for agricultural purposes, that “one day” never arrived.

Georgeson first allowed use by the Alaska Division of the U.S. Bureau of Education, but division personnel didn’t really need it. Permission was also given to a U.S. commissioner to use the station’s main house, but it appears he seldom, if ever, exercised that right. Some Seward freighters were allowed to store their horses in the station’s barn for a while. And education personnel, without proper authority to do so, allowed a local storekeeper and hunting guide to live in the main house rent-free—until Georgeson learned about it.

In 1912-13, the U.S. Forest Service asked for permission to use the station grounds and outbuildings for a new ranger station in Kenai, and Georgeson granted that request. What followed were months of back-and-forth letter writing as officials negotiated terms, smoothed the ruffled feathers of those who had been involved in previous usage, and ironed out crucial details of responsibility moving forward.

Unfortunately for Georgeson, Forest Service officials changed their minds. In July 1914, the service informed Georgeson that for it, too, Kenai’s inaccessibility was a problem. The idea of a Kenai ranger station was shifted, instead, to Ship Creek, where plans were in place for a new railroad depot and where the city of Anchorage was about to spring into life.

Before the Forest Service exit, however, forest ranger L. Keith McCullagh offered some comments and observations that became the likely impetus for important changes in the early 1920s to the station grounds.

First, McCullagh recommended a local man, Fred W. Johanson, who he believed could be a reliable caretaker for the Kenai Station until the U.S. Department of Agriculture decided what to do with its resource.

Johanson wrote a personal letter to Forest Service officials, and Georgeson later promised to communicate with him and see if an agreement could be reached, but whether any contract was made between the two is unknown.

Second, McCullagh observed that the village of Kenai was becoming crowded and that many people seeking new building sites were being forced to locate “out in the wilderness.” The Kenai Station occupied 320 acres, most of it unused, and the Russian Orthodox Church also owned a sizable swath of adjacent land, effectively blocking village expansion to the north and northwest and virtually pinning Kenai residents inside a narrow piece of high, eroding bluff above the Kenai River mouth and Cook Inlet.

Already, McCullagh said, at least local three men were building structures on or across station boundaries.

“I am strongly of the opinion that a certain portion of the [station] tract should be eliminated for [i.e., opened to] the use of Kenai residents for building purposes,” wrote McCullagh to Forest Supervisor William G. Weigle. He offered to map the station borders and recommend a large section of this federal land “to be set aside from the Chugach Forest as a Townsite.”

Informed of McCullagh’s suggestion, Georgeson replied, “Neither I nor anyone else other than the President of United States has any authority to either add to or take from the reservation once established by executive order.” Anyone violating that original order, he continued, would be trespassing and subject to legal action.

On Jan. 12, 1921, however, a new executive order, signed by Pres. Warren G. Harding, did create the change McCullagh had suggested. When the virtual dust had cleared, the Kenai Station grounds had shrunk to 5.42 acres—essentially the site of the station buildings and its two water wells. Originally, this smaller parcel extended just south of the location of today’s Overland Avenue.

The remaining station land, more than 300 acres, was restored to the public domain.

Much of the history of the remaining Kenai Station has proven difficult to trace effectively through the years, but it appears that the Alaska Game Commission, created by an act of Congress in 1925 to protect and manage game and fur-bearing animals and birds in the Territory of Alaska, was the next government entity to occupy the site. Some sources indicate that the building now marked 502A—or at least some portion of it—was built for the commission during the late 1930s.

A mid-year report for the Alaska Game Commission in 1937 noted that there was a “partially constructed headquarters [building]” in place in Kenai, and that, with the aid of the Civilian Conservation Corps, completion of this structure was expected during the winter of 1937-38. It is also likely that the commission shared this headquarters with the federal Bureau of Biological Survey, which at this time was still a part of the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

The final occupants

On Dec. 16, 1941—just nine days after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—Pres. Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed into existence the Kenai National Moose Range. It would be seven years, however, before anyone was hired to oversee the operations there.

In December 1948, David L. Spencer was brought on board as manager—mostly to survey the refuge’s vast resources and to tamp down the rampant poaching problem, which had been exacerbated by the 1947 construction of the Sterling Highway and a sudden influx of new homesteaders, within moose range boundaries.

A new field station for Spencer and for his first enforcement officer, James Dale Petersen, was established on the old Kenai Station site. John Hakala was brought in as a biological aide for the summers of 1950 and 1951; years later, he would become refuge manager.

According to a 1997 interview with Hakala, by Carol Ford, he remembered, on-site, an old log building that he had been told was the original Kenai Station quarters. Initially, he and his wife, Mae, were housed in this structure, which he said had no door in its frame and “solidly fly-specked” windows. To keep out the weather, he hung his “rain parka” over the gaping doorway.

That was likely the final legitimate use of that building, which was probably the last of the original log buildings once erected on the grounds. Photos from the late 1940s do show the old Kenai Station quarters; photos from the early 1950s do not.

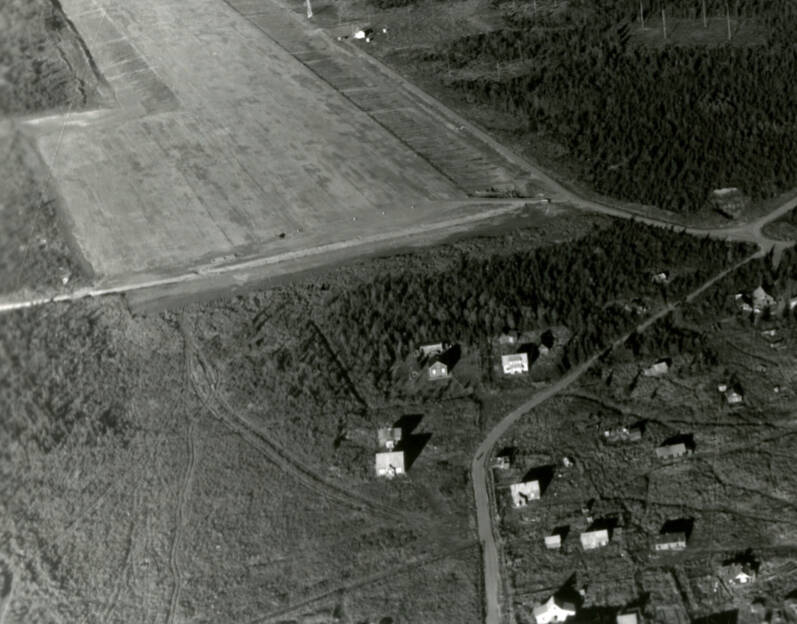

Considerable new construction occurred on-site in late 1948 and over the next several years, beginning with the importation of four war-surplus Pacific Huts (like Quonsets) from Kodiak and concluding with a large multi-bay garage and storage building. For a few years, both Spencer and Petersen and their wives lived here. In 1963, the federal government officially changed the designation of this place from field station to headquarters.

What soon became known as the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service occupied the site until about 1980, when a new headquarters was constructed on refuge property atop Ski Hill Road near Soldotna.

After the departure of refuge personnel, local entities argued about its future use, with some contending that it should become the home of a new Kenai museum.

Instead, it was controlled by the Bureau of Land Management until December 1998, when it was turned over to the Kenai Natives Association. Today in front of building 502A, only the historic marker, containing minor inaccuracies, hints at the long and complicated saga that was once played out on this location.