AUTHOR’S NOTE: Stephan “Steve” Melchior had parleyed a partially fabricated past into a respected life as a miner and builder in Alaska. He had arrived in the Territory in the mid-1890s and spent the remainder of his life on the Kenai Peninsula.

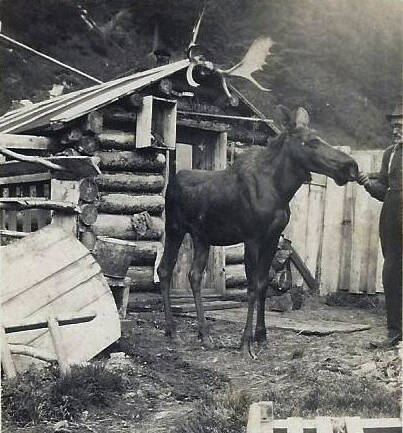

In April 1924, a Pathé News staff photographer passed through Seward and photographed Steve Melchior with his young pet moose, Elsie. Melchior had discovered her, orphaned, along the middle Kenai River above Skilak Lake. After a powerful flood in 1923 had wiped out his moose-ranching operation there, he had brought Elsie to his property in Seward and begun to stay permanently there. He lived in his old cabin and kept Elsie enclosed in a 6-foot-high pole corral.

Occasionally, Melchior drifted back to his old Surprise Creek placer mine or went hunting in the hills with friends, but he spent most of his time in town, where his cabin was equipped with woodworking tools. There, he built furniture and constructed boats, while tending to his still-growing moose companion, often charging tourists a small fee to view her feeding or performing tricks.

By May 1928, however, Melchior was 70 years old and wearying of the constant struggle to keep Elsie fed. Repeatedly, he was forced to hitch his dog team to a wooden wagon and trundle off for birch or willow saplings, and he told the Seward Gateway, “I can’t stand this daily foraging the woods.”

He put Elsie up for sale. “Here is a chance for someone to procure a fine, live specimen of a moose at a reasonable figure,” he said to a reporter.

He advertised in several newspapers: “Situation wanted. Two-year-old lady moose desires quiet home.” Elsie was at least five years old by this time, fully mature and requiring considerable amounts of food and attention.

Adopting a pet moose was a difficult proposition, but by September he had a taker: the Detroit Zoological Park at Royal Oak, Michigan. The zoo already had two moose — one bull and one cow, imported from eastern Canada — but it was looking for a third to boost breeding prospects. The caveat to the deal was that someone would have to manage Elsie’s transportation to the Midwest. Zoo officials commissioned Melchior to do the job.

Planning his first trip out of Alaska in more than three decades, Melchior crafted a wooden crate, lined with old mattresses and quilts, that was large enough to safely hold his 1,240-pound pet. He planned to have her hoisted aboard a steamship leaving Resurrection Bay for Seattle, where she would then be loaded onto an eastbound train.

This moose-and-man journey attracted considerable attention nationwide.

Newspaper articles often included Elsie’s “origin story,” concerning her rescue by Melchior after a brown bear had killed her mother. Suspecting that a calf may be lingering near the cow’s remains, Melchior had searched for and found the spindly 17-pounder and managed to bring her home with him.

The Seattle Post-Intelligencer ran a story along with a photo of Melchior feeding Elsie. Around the same time, the Spokane Press offered an article about “one of the strangest couples to pass through Spokane on a Northern Pacific train.” The paper claimed that Melchior was 78 years old and referred to him as “a grizzled old sourdough who has spent 35 years searching for gold.”

The Detroit News placed a photo of Melchior and a separate image of Elsie on the front page of its Oct. 14 edition. An accompanying story related the chaotic greeting Elsie received from the two resident moose and Melchior’s assurances that, despite appearances, the three moose would soon become friends.

Back home in Seward in November, Melchior was interviewed by local reporters about his trip. And the man who had perpetuated so many falsehoods during his life focused on the inaccuracies about himself in other newspapers. “People seem to know more about myself than I do,” he remarked in the Seward Gateway.

He found it particularly interesting that, although he said no one on his trip had asked him about gold mining, one newspaper claimed that “many” people had made such inquiries. He said that other “wild newspaper yarns were concocted” as well, but he seemed to find them more amusing than irritating.

Meanwhile, back in Bellingham

In the mid-1890s in Washington, Steve Melchior had abandoned his wife Katherine and their five young children (two adopted daughters and three biological sons) and had fled to Alaska. A year or so later, he had sent a coworker to Katherine to tell her that her husband had died in Alaska.

Believing herself a widow for a second time, Katherine had spent more than a decade as a single mother, working in a laundry to feed, clothe and house her children; however, tragedy never drifted far from her door. Although she remarried happily in 1908, her eldest son John was discovered dead — a victim of either suicide or murder — early in 1909.

Three months later, a woman named Christina Adams filed a lawsuit for “breach of promise” against Katherine’s new husband, Michael Fliegenbauer. Adams claimed that she had in December 1906 “secured (Fliegenbauer’s) promise” to marry her, and he had broken that promise by marrying Katherine, instead.

Adams said in court that she was suffering “because of lacerated feelings, wounded spirits and loss of opportunity to become head of (a) family of wealth and social distinction.” Although the final outcome of the suit has yet to be discovered, it seems likely that it was dismissed by the court as frivolous.

In 1924, the youngest of Katherine’s two remaining daughters (two others had not survived childhood) died accidentally. Thirty-four-year-old Margaret, who had been considered an invalid because of spinal meningitis, drowned while attempting to board a gas boat from a dock in Vancouver, British Columbia.

Margaret was descending to the vessel when the ladder overturned and dumped her into the sea. She was dragged from the water within minutes but could not be resuscitated.

Then, four years later, while perusing a Washington newspaper, Katherine learned that her supposedly deceased second husband was still very much alive. The stories and photos depicting Steve left no doubt.

According to one grandson, she was “horrified” to learn the truth. She also worried that her neighbors would consider her a bigamist, even though she was the one who had been deceived.

Katherine’s middle son, Frank, was studying to become a chiropractor and would spend the rest of his life across the country in Pennsylvania. Her youngest son, William, had in 1926 ended a brief, unhappy marriage by filing for divorce on the grounds of cruelty. Only her eldest daughter, Marie, still lived in the area and remained contentedly married.

Katherine’s third husband, Michael, died in 1929.

By early 1932, Katherine, probably suffering from dementia, was placed under Marie’s guardianship and declared “incompetent.”

She died on March 14, 1937, at the age of 80, in Snohomish County, Washington.