AUTHOR’S NOTE: Stephan “Steve” Melchior parleyed a partially fabricated past into a respected life as a miner and a builder in Alaska. He arrived in the Territory in the mid-1890s and spent the remainder of his life on the Kenai Peninsula.

The Seward Gateway newspaper reported in August 1921 on this announcement from the office of Alaska’s territorial governor: “A special permit has been granted Stephen Melchior, of Seward, for the capture of calf moose on (the) Kenai Peninsula…. Mr. Melchior, it is stated, plans an experiment in the domestication of the animals. The permit gives him the authority to take one male calf and three female calves for propagation experiments and for exhibition purposes.”

This special permit simply made legal an activity in which Steve Melchior had apparently been indulging — on and off, anyway — for years.

In 1912, U.S. Forest Service ranger Keith McCullagh had photographed Melchior’s “semi-pet moose” at Melchior’s Landing (a crossing point on the middle Kenai River, situated above the canyon and known today as Jim’s Landing). “This moose,” wrote McCullagh in his ranger diary, “lay around all day in the warm sun close to us, and we were enabled to walk up to within 15 feet of him before he would manifest the least interest.”

In June 1913, a peninsula game warden informed the governor that Melchior was raising a moose calf on his mining property. “Melcher [sic],” wrote the warden, “states he found a cow and calf dead (killed by a brown bear) and along with them the live calf which he took home…. He is feeding the calf on condensed milk, three cans a day, which he has to pack on his back for seven miles.”

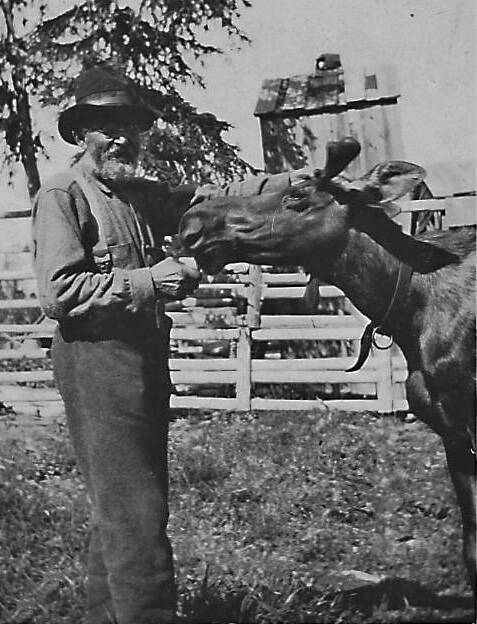

In 1920, a year before the special permit was issued, he took in a young bull moose and named him Tommy. By 1922, he had trained Tommy to pack supplies. When young George Beebe Roberts showed up to work for the summer for Melchior, Tommy already had his own small pole corral on Surprise Creek, and Roberts helped construct additional fencing to hold future moose.

Interestingly, wrote Roberts in a 1950 article about his experience in the Alaska Sportsman Magazine, Melchior said his special permit allowed him to capture and keep up to eight moose calves. Additionally, he wrote, “With this foundation stock (Melchior) planned on building up a business in supplying specimens of this monster species to parks and zoos over the world.”

Besides expanding the corral system, the two men scouted for future habitat on which future calves could browse and graze. Some of that habitat appears to have included the flats in the lower Kenai River canyon where former Melchior neighbor, Herman Stelter, had had his home. Stelter had lived and mined on and below the river’s confluence with Surprise Creek from about the turn of the century until 1917, when a heart condition forced him to abandon his property to seek medical attention. Stelter had died in California in 1918.

Mamie “Niska” Elwell, who lived for many years with her husband Luke at their fishing lodge on Upper Russian Lake, knew Melchior well, and she also, like Roberts, wrote about his moose-ranching efforts in the pages of the Alaska Sportsman Magazine. She said that Melchior’s primary corral was “built athwart the main moose trail near the Kenai River.”

“His corral,” wrote Elwell, “had elevated gates, with a complicated system of weights and counter-weights, like a Rube Goldberg contraption, so they closed after a moose entered the pen. By this device, Steve captured full-grown animals. The moose calves he kidnapped from their mothers out in the open.”

Melchior told Elwell that he had initially tried feeding calves with Eagle Brand milk, but it seemed too sweet for them. Eventually, he settled on ordinary condensed milk that he diluted with water and heated.

By the time trouble hit at the moose ranch in the fall of 1923, Melchior had at least three moose in captivity and appeared to be holding them on or near the old Stelter property as winter approached.

The big flood

During the first week of October, the natural dam holding at bay a glacial lake at the foot of the Snow Glacier broke loose, sending a surge of water down the Snow River and into the upper end of Kenai Lake. This influx, combining with unusually heavy precipitation that had begun around the last days of September, caused a deluge on the Kenai River below the lake.

“Continuous heavy rainfall for the past week,” reported the Seward Daily Gateway on Oct. 5, “has caused a washout along the Alaska Railroad at many points. At Mile 3¼, the bridge went out at noon today. At Mile 13 and 14, the waters from Snow River have covered the grade…. The past week of rain was the heaviest seen in this vicinity for many years.”

A week later, the rain was still coming down. The newspaper referred to “torrential rains of the past 30 hours” that had “flooded the country.” It was estimated that at least 11 inches or more of water had fallen in just over a day and a half.

Because of Steve Melchior’s penchant for exaggeration and mistruths, it is difficult to truly measure the effect that all this water had on his moose ranch, but it was clearly devastating.

Mary J. Barry, in the second volume of her trilogy on the history of Seward, wrote that Melchior’s cellar was filled with water and gravel, damaging his cabin, which was lifted off its foundation, and burying his supply of canned vegetables and jellies and his other supplies.

The moose Tommy, she said, “went wild during the high water. He knocked down the tent with his antlers and attacked Melchior. Until that time, Tommy had been very tame, except during rutting season.” Melchior, wrote Barry, was forced to shoot and kill his prize bull in order to save himself.

Melchior had two other moose that he had been taming, she said. He chopped down a portion of their corral to allow them to flee, and one of them drowned trying to escape the flood waters. He managed to rescue a single young female, whom he called Elsie.

Nine years later, he would tell visiting German sailor Carl Kircheiß that, because of his distrust of banking, he had been safeguarding his gold in his home. He claimed to have lost $30,000 worth in the flood, managing to find only two gold coins of the fortune he had squirreled away. It was a particularly tragic loss, he told Kircheiß, because he had been thinking seriously about selling his claims, taking his money and moving back to Germany to spend his old age.

By November, he had managed to bring Elsie to his cabin in Seward and he built there a small pen in which to keep her. Elsie, who almost instantly became a tourist attraction and a small source of income, was the last moose that Melchior would ever own. And the end of her time with the old miner would finally expose the falsehood upon which the end of his marriage, about three decades earlier, had been based.