AUTHOR’S NOTE: An adulthood constructed on a web of lies eventually led Stephan “Steve” Melchior to leave his wife and five children (two adopted daughters and three biological sons). He departed for Alaska and spent the remainder of his life on the Kenai Peninsula.

Steve Melchior, after abandoning his wife and children in Washington in the mid-1890s and settling into a life on the Kenai Peninsula, seemed to disappear, perhaps on purpose. Melchior may have preferred to keep his existence on the downlow and emphasize the lie that he had died in the Last Frontier.

The first known, specific, contemporaneous mention of his existence in Alaska occurred in the 1910 U.S. Census for Seward. After this point — with the abandonment of his family 15 years in his rearview mirror — his name and his movements began appearing with some regularity in newspaper articles and other official documents.

Some of his early Alaska actions can be determined by backtracking through later paperwork, while other movements, particularly from 1896 until 1906, remain unknown. The difficulty of any search for evidence about Melchior, regardless of the time period, is exacerbated by the facts that he answered to Stephan, Stephen and Steve and his surname was so often misspelled. Even his hometown Seward newspaper often transposed the “o” and the “i.” Other variations included Melchor, Melcher and even Mulscher.

When British big-game hunter Morris L. Parrish pursued moose and Dall sheep in the highlands between Skilak and Tustumena lakes in 1912, he was led by well-known guide Andy Simons. In mid-September, Simons brought Parrish to what he called “Steve Melcher’s Cabin,” near timberline on the upper portion of the Killey River. Simons told Parrish that the small spruce-and-cottonwood-log structure, standing on the west bank of the stream, had been built six years earlier.

At the time of Parrish’s hunting expedition, Melchior was no longer using his Killey River cabin. In fact, Parrish referred to the cabin as “abandoned.” Although other men continued to use the cabin for many more years, Melchior had already moved on.

His energies now seemed to move in two different directions — to the fledgling town of Seward and to placer mining on a tributary of the middle Kenai River.

Town and Country

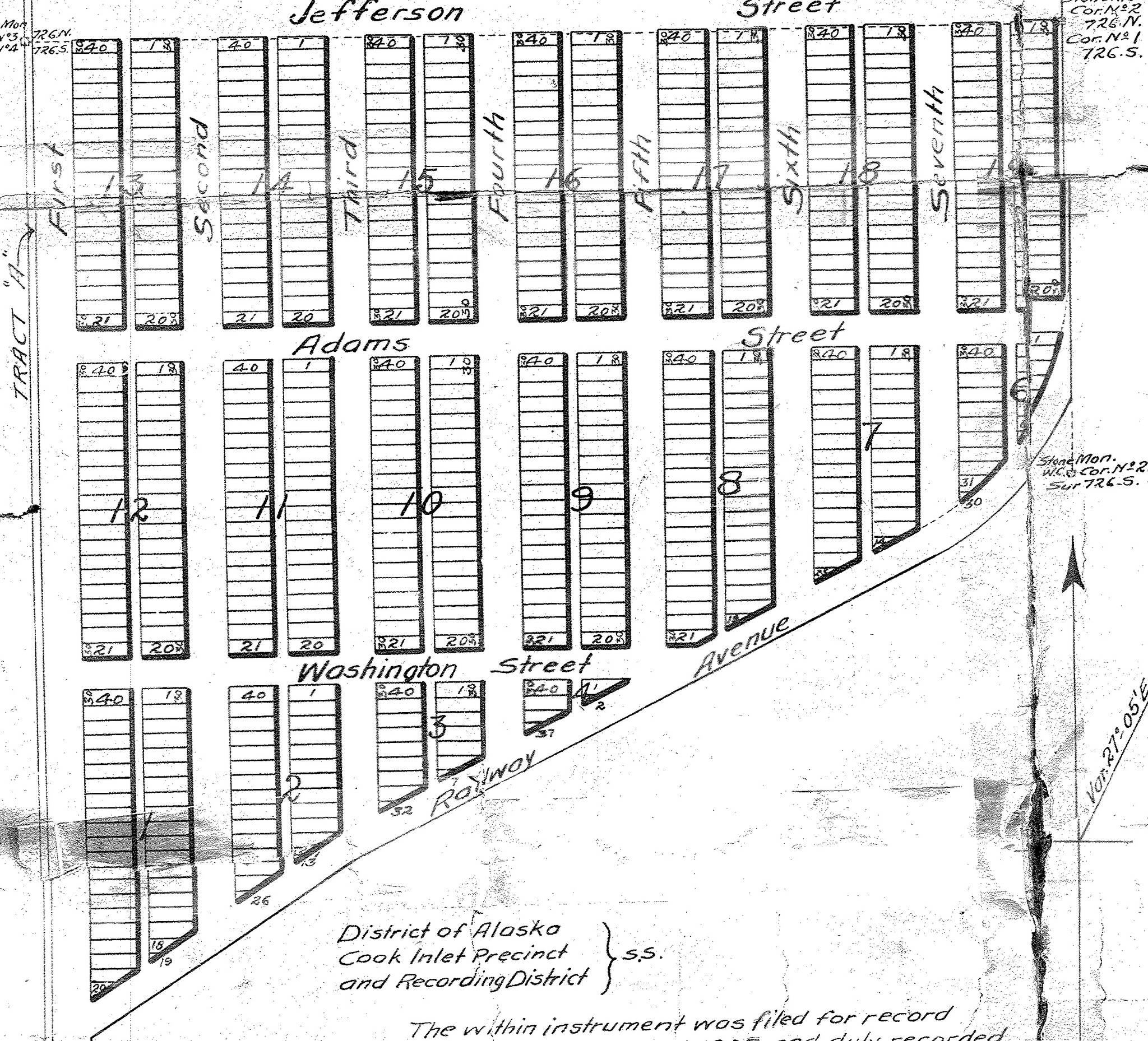

The townsite of Seward was founded in 1903 when efforts began in earnest to connect ice-free Resurrection Bay to a planned new railroad system into the interior of the Territory of Alaska. The delta on which the City of Seward now sits was divided into grids and building lots, and construction began.

Property disputes were inevitable, and one of them, in 1917, involved Steve Melchior. On Aug. 17, the case of “John A. Noble vs. Stephen Melchoir” [sic] was under way in district court to determine the ownership of lots 21, 22 and 23 of Block 12, on which, according to the Seward Gateway, “Melchoir (had) resided for some time.”

Melchior claimed ownership of the lots by “prior right,” said the newspaper. “The lots are part of the survey of the townsite of Seward and have passed through various hands, according to the records. Melchoir, however, paid taxes on the property for several years.”

The plaintiff, John Noble, argued that he had purchased the property legally in 1915 from Seward founder John E. Ballaine.

The case went to Judge Brown, who ruled in Melchior’s favor. “The judge,” said the Gateway, “decided that Melchior had entered the lots when he still had a right to do so, and had held them adversely for more than 10 years after Frank Ballaine (brother to John Ballaine) received patent to them.”

According to the judge, Melchior had settled on the lots at least as early as 1907. He also built a small log cabin on the property and lived there when he was not busy placer mining. Melchior would retain his ownership rights until his death in 1933.

It is uncertain when Steve Melchior left his Killey River cabin and began mining on Surprise Creek, which drains into the Kenai River in the canyon above Skilak Lake, but speculation is possible based on the 1912 observations of U.S. Forest Service ranger Keith McCullagh when he and forest guard Jack Brown performed a forest reconnaissance in the area.

Traveling on foot and by dog team in early February, according to McCullagh’s ranger diary entries, he mentioned “Melchors landing,” a reference to Melchior’s crossing point, just above the canyon, on the Kenai River — a point known today as Jim’s Landing, named for two miners (both named Jim) who took over Melchior’s old mining claims in about 1935.

By this point in time, Melchior already had an extensive placer-mining operation going at about 800 vertical feet above the river. There, said McCullagh, Melchior had constructed a derrick and a sawmill, both run by water power. “The saw mill,” McCullagh wrote, “is a very ingenius [sic] affair, so arranged that one man can run the whole plant. Melchor [sic] found the derrick a necessity in removing the large boulders with which the creek abounds.”

Melchior had constructed a home cabin in which he lived during the mining season, and there were also sluice boxes, a system of trails, and a two-mile-long mining ditch for water diversion. Such infrastructure must develop over a period of time. It has been suggested that Melchior may have started his work on Surprise Creek as early as 1907.

Interestingly, McCullagh added: “There are two groups of mining claims on this creek, (one) above timber line and one of 800 feet elevation, the latter being worked by Steve Melchor.” The other Surprise Creek miner was, like Melchior, also a German immigrant — Herman Stelter, one of the members of the ill-fated Kings County Mining Company expedition. For many years, Stelter and Melchior were likely neighbors of a sort.

While Melchior mined the middle portion of the creek, just below timberline, Stelter worked closer to the stream’s headwaters. Later, it appears, Stelter abandoned the higher-elevation claims to focus solely on claims nearer the Surprise Creek mouth, just above his home in the lower canyon.

Since about the turn of the century, Stelter had lived on the flats inside a meander near the canyon outlet. McCullagh wrote that Stelter had cultivated the flats, raising potatoes, lettuce, radishes, beans and peas “in profusion.”

“The gently sloping benches below Stelter’s about one mile from the head of Skilak Lake, now covered with a splendid stand of birch,” said McCullagh, “would be easily adaptable for agriculture, being fairly high, well drained and possessing soil of a deep sandy loam.”

Stelter continued to live and work there, probably year-round, until 1917 when a heart condition spurred him to travel to California for medical treatment. He died there in 1918, and it seems likely that Melchior utilized his neighbor’s property for a moose-ranching operation that will be discussed later in this series.

McCullagh also seemed to imply that, at least by 1912, Stelter was having better mining success than Melchior, whom McCullagh said was making “small cleanups every season.” Stelter, he wrote, “takes out a tidy little sum each season which is salted away in glass jars and tin cans in his cellar.”

Melchior filed a water-rights claim on Surprise Creek on May 16, 1912, just 10 days after Stelter filed on two placer-mining claims — one called “Cabin Claim” because of its proximity to his home, and the other called “Punk Claim,” for reasons that are unclear.

Melchior filed no mining claims on Surprise Creek until 1916 and 1918.

Although the two men had to be aware of each other and were perhaps even friends or acquaintances, no known references to the two of them sharing anything other than geographic closeness and a German heritage has yet been found.