AUTHOR’S NOTE: An adulthood constructed on a web of lies eventually led Stephan “Steve” Melchior to leave his wife and five children (two adopted daughters and three biological sons). He departed for Alaska and spent the remainder of his life on the Kenai Peninsula.

After abandoning his wife, Katherine, and their young children in Washington and escaping his responsibilities by moving to the Last Frontier, Stephan “Steve” Melchior sent a friend to Katherine to tell her that he had died in Alaska.

Katherine, a Slovenian immigrant (from the Austrian Empire) who had been widowed by her first husband just before she moved to the United States, now believed herself a widow for a second time. Because her first marriage, until its tragic conclusion, had been a happy one — as opposed to the tumultuous relationship she had had with Stephan — she decided to return to her prior married surname, Stark, the Americanized version of Šterk. Her daughters, too, became Starks once more, and she changed her sons’ surname to match.

Left to fend for herself, she spent years washing neighbors’ clothes to provide her children with food and shelter. In the 1900 U.S. Census, she was listed as a resident of New Whatcom, Washington, as an employee of a laundry, and as a single mother of five children (Marie, age 20; Margarite, 14; John, 12; Frank, 10; and William, 8).

In July 1908, at the age of 52, she remarried. She and Michael Fliegenbauer wed before a Justice of the Peace in Bellingham and remained together until Michael’s death more than 20 years later. By 1910, only two of Katherine’s children, Margaret and William, were still living at home.

Settled at last in a happy union, Katherine would still fail to find complete peace. One of her sons and one of her daughters would die before she did, and then, in her early 70s, she would learn that Stephan Melchior had not died, after all, in Alaska.

Melchior, for his part, would never come clean about his only marriage. Not even in his final years, as a respected resident of Seward, would he admit the truth.

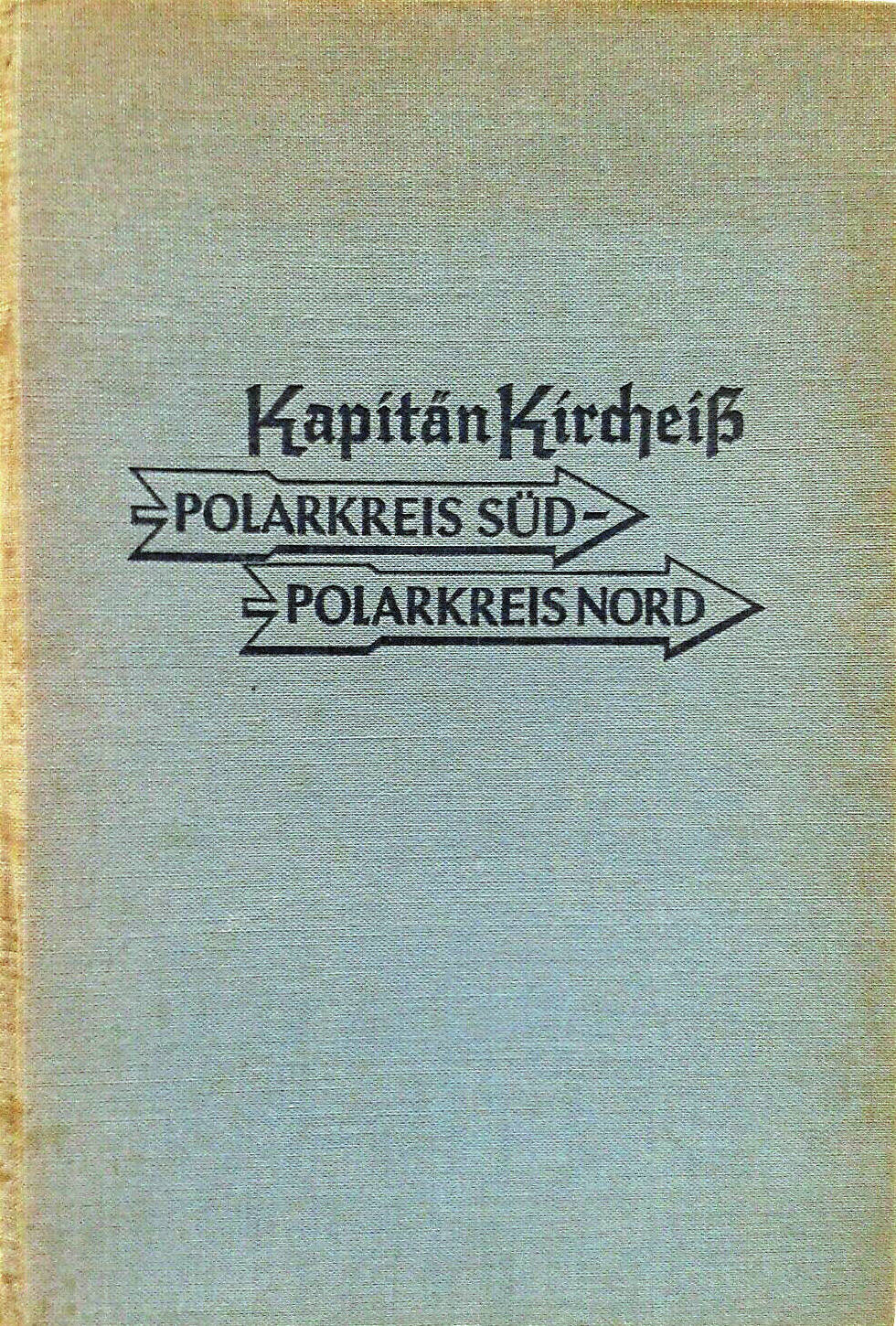

In 1932, one year before his death, he was visited in Seward by German-born Capt. Carl Kircheiß, who had circumnavigated the globe a few years earlier and was, at this time, exploring parts of the world as a passenger on a fishing vessel. After sailing into Resurrection Bay, Kircheiß heard that several German expatriates were residents of the Gateway City. When he visited Melchior’s small cabin in downtown Seward, Melchior described his marriage, and Kircheiß recorded the description in his memoir, Captain Kircheiß: Arctic Circle North – Arctic Circle South:

“I married an Austrian woman (said Melchior). I loved and spoiled her; it’s my own fault she became vain and extravagant. In nine years, she spent $45,000, plus my annual income of $6,000 to $10,000, and I loved this spendthrift woman until she became unfaithful to me…. I then knew that to buy milk is cheaper than to keep a cow.”

No sentimentality there, and only a modicum of truth. He told the captain that he had divorced Katherine after her alleged infidelity.

Melchior also told Kircheiß that he had settled in Alaska in 1894, which was only about seven years — not nine — after he had gotten married.

It is difficult to know precisely when Melchior made Alaska his permanent home. Sources vary between 1894 and 1896. His 1933 obituary in the Seward newspaper claimed that it was 1896, when he sailed from Puget Sound to Alaska — probably into Resurrection Bay — in a vessel he had designed and built.

Certainly, Melchior had the skill to build seaworthy boats. He would prove his craftsmanship repeatedly over his decades in Alaska. And certainly, the timing is about right for the arrival of a man in search of riches, as the discovery of gold in the Klondike occurred in the autumn of that year.

That said, it is known that March 13, 1894, was the date of Melchior’s last mortgage payment on the 158 acres he had agreed to purchase in Mason County, Washington.

By November 1897, a series of legal ads appeared in the Mason County Journal on behalf of plaintiff Elizabeth E. Bachman, who asked the court to allow her to foreclose on the land she had agreed in February 1893 to sell to Melchior. According to the ad, if Melchior failed to show up in court by an appointed time and pay what he owed, he would forfeit the land and whatever equity he had in it.

He did not show up.

In February 1898, the judge in the case found in favor of the plaintiff. Melchior owed $293, which he never paid. He also owed and never paid $50 in attorney fees, $34 in taxes and $18 in plaintiff’s costs, plus the cost of running a Sheriff’s Sale in April. At the sale, any property found to belong to Melchior was auctioned off to cover some of the costs.

The John Stark tragedy

As Stephan Melchior (now going almost exclusively by “Steve”) was exploring Kenai Peninsula streams for potential placer claims, and his newly remarried “widow” was beginning to enjoy her new life as Katherine Fliegenbauer, a family misfortune was unfolding.

In the summer of 1908, 19-year-old John Stark (born Johannes “John” Melchior and the eldest son of Katherine and Stephan) worked as a cook at the Pacific American Fisheries traps at Bush Point in Puget Sound. After the fishing season, he began a course at a business college. He had been helping his mother financially, but her new marriage made that assistance no longer necessary. He did, however, continue to live in his mother’s home in Bellingham.

On Dec. 16, in response to a letter from an unnamed friend, the now 20-year-old Stark traveled to Seattle to meet the letter-writer, who had offered him employment. When he returned on Dec. 18, he told his mother that he had secured a good job in a Seattle lodging house.

On the morning of Dec. 19, with $85 and a revolver in his pockets, Stark went into Bellingham to meet again with the Seattle friend, announcing that he expected to return home in time for dinner. His family never saw him alive again.

His remains were discovered near the Bay View Cemetery on Feb. 4, 1909. Authorities initially termed the death a suicide.

His mother refused to accept that her quiet, industrious son had taken his own life. In a lengthy article in the Bellingham Herald on Feb. 5, she argued that her son had been murdered. Except for a five-cent piece, all of the money Stark had taken with him on that last morning was gone.

Stark’s youngest brother, William, helped identify the badly decomposed body when he recognized John’s gun and hat. Named among John Stark’s survivors, besides William and his mother, were his two older half-sisters, Marie (married and living in Alberta, Canada) and Margaret (“an invalid, who resides at home”). For some reason, middle brother Frank was not mentioned, and neither was John’s biological father, Steve Melchior.

How and when Melchior learned of his son’s death is unknown, but he did find out. The death was summed up this way in Melchior’s obituary: “A son, John, died about 25 years ago.”

Although obituaries can be notoriously inaccurate, Melchior’s knowledge of his family seemed thin. He was said to have been survived by one son and one daughter. The son, Frank, was “believed to be somewhere in the East.” The daughter, whom the obit called “Billie,” was said to be married, known as “Mrs. Stevens,” and lived in Seattle.

The familial severance appeared almost complete.