AUTHOR’S NOTE: Locating the physical site for the administration efforts of the Kenai Peninsula Borough on Binkley Street in Soldotna was one thing. Before that came the competitive process of deciding where the seat of borough government should be.

Contentious baby steps

On March 31, 1962, at a public meeting of the Kenai Peninsula Borough Study Group — held nearly two years before the borough officially existed — former Kenai marshal and Alaska territorial legislator Allan Petersen offered to donate 5 acres of “choice” homestead land in the Kasilof area to provide a location for the construction of borough offices.

On April 13, in a letter to the editor of the Cheechako News, Kasilof resident Homer Browning wrote to offer 5 of his own acres for the same purpose. “I read your paper with interest, and take the citizen’s viewpoint that the borough should be easily accessible to everyone,” Browning said, “and my land is on the main highway, two miles north of the Kasilof River bridge.”

The generosity of these two men resulted from the conclusions of the Study Group, which at that four-hour March 31 meeting established the following tenets: (1) Legislative election districts 9 and 10 will comprise the new borough. (2) The borough will seek first-class status. (3) The new government entity will be called the Kenai Peninsula Borough. (4) The borough seat will be established within a 3-mile radius of Tustumena.

The decision to locate the borough seat in or near Tustumena was termed by the Cheechako as “perhaps one of the most surprising incidents at the meeting.” Although Kenai, Soldotna and the Sports Lake area were also mentioned as possible sites, Tustumena was selected because the group voted to place the borough seat on “neutral ground,” near the Tustumena School.

Members of the Study Group explained that the Tustumena location would help unify the entire peninsula, thus avoiding the differences that might arise between neighboring communities if one of the larger towns were selected.

Ultimately, however, the choice of largely undeveloped Tustumena would not prove satisfactory, and several larger peninsula communities would battle over where to place the seat of government — just as they would battle over many aspects of the borough in the years to come.

In October 1961, two and a half years into statehood, the Alaska State Legislature passed the Borough Act, essentially transforming Alaska into one giant Unorganized Borough. Residents of the state were given until July 1963 to form their own organized boroughs, thereby establishing the sizes, boundaries, government seats and tax bases for those boroughs. Areas not formed into organized boroughs would remain — and still do remain — part of the state’s Unorganized Borough.

First to incorporate was the Bristol Bay Borough. Today the state contains 18 organized boroughs, while the rest, the Unorganized Borough of Alaska, encompasses more than half of the state and has a population of more than 80,000, including residents of Dillingham, Valdez, Cordova, and its largest city, Bethel.

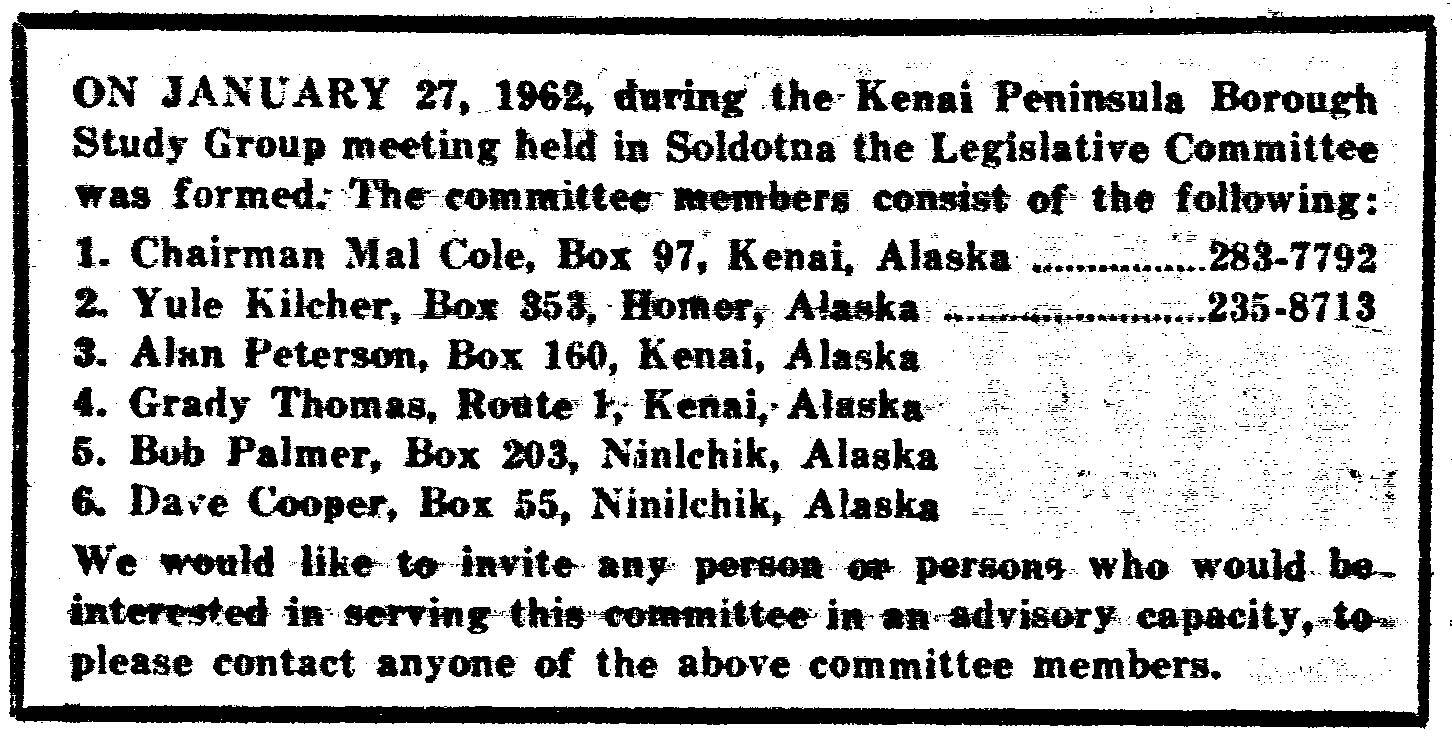

After the passage of the Borough Act of 1961, many communities around the state began to scramble to meet the July 1963 deadline. The Kenai Peninsula Borough Study Group formed on Jan. 27, 1962, and quickly took action, facing diversity of opinion and divisiveness from the start.

The March 30, 1962, edition of the Cheechako News urged peninsula citizens to attend the next day’s Study Group meeting, which was to be held after a noon luncheon at the Riverside House restaurant in Soldotna.

The Cheechako’s headline promised verbal “fireworks,” and the paper had good reason to believe that sparks might fly.

For one thing, the city of Homer was not yet advocating a peninsula-wide borough. There was talk of the peninsula containing at least two boroughs and possibly more.

Peninsula residents also disagreed over whether the new borough should have first-class status or second-class, and what the new borough should be called.

The Kenai Chamber of Commerce, for instance, favored a first-class borough named “Kenaitze,” with its seat in Kenai.

Other names suggested for the new borough included Tustumena, Cook Inlet, and Progress.

After what the newspaper called “a lengthy and somewhat turbulent session” on March 31, the dust settled briefly. The tenets set forth that day by the Study Group were non-binding; they were considered preliminary steps in the process of filing an application for a borough with the state’s Local Boundaries Commission and Local Affairs Agency.

Still, there remained some sense of urgency. Although the KPB Study Group was the largest group studying borough organization, there were other active groups — in the Homer and Fritz Creek areas — with different agendas. There was talk of a Homer Borough or South Peninsula Borough, but many opponents of the idea wondered aloud what the south peninsula hoped to use for an adequate tax base.

Besides, some noted, the south peninsula itself wasn’t unified; the residents of nearby Ninilchik, for instance, favored a whole-peninsula plan.

And then there was the Anchorage problem. Many residents feared that the entire peninsula, despite the discovery of oil and natural gas in recent years, lacked the tax base to survive as a borough on its own. This fear led to another: that a larger borough, say one centered more broadly on Cook Inlet and headquartered in Anchorage, might “swallow up” the peninsula.

By June, the Study Group had decided by a 6-5 vote to petition for second-class borough status, instead of first-class. About a week later, the group nixed its whole plan, said it needed more study, and went back to the drawing board.

As the July 1963 deadline approached, the Bristol Bay Borough remained the only organized borough in the state, and the pressure increased on areas still in the planning process. The State Legislature then passed the Mandatory Borough Act, which was signed into law by Gov. William A. Egan in April 1963, and which required all state election districts over a certain population threshold to incorporate as boroughs by Jan. 1, 1964.

The regions thus required to form boroughs were in or near Anchorage, Fairbanks, Juneau, Ketchikan, Sitka, Kodiak Island, the Matanuska-Susitna valleys, and the Kenai Peninsula.

On April 20, 1963, residents from across the peninsula converged at a heavily attended meeting in Soldotna to determine the exact boundaries of the borough. At the meeting, after considerable discussion and no real progress — Homer again raised the idea of its own borough, and the idea of a Seward Meridian Borough was posed — Frank Mullen made a motion to let the state decide the borough’s boundaries.

Discussion was apparently heated. Another motion was made to table Mullen’s motion, but the tabling motion was voted down. A vote was then taken on Mullen’s motion, which passed 31-24.

About a week later, at another meeting at the Riverside House in Soldotna, it was announced that the state had refused to do the peninsula’s work on boundary-setting. The onus was back on peninsula citizenry.

In May, a group of Kenai citizens filed a petition for a first-class borough that included only Kenai, Nikiski, Soldotna, Sterling, Kasilof and Tustumena areas. Later that same month, the Homer Borough petition was rejected by the state’s Local Boundary Commission because it lacked sufficient signatures, and the pieces fell together, at last, for a united front. The Kenai Peninsula Borough would be a peninsula-wide entity with an elected executive officer called a chairman.

An election was held Dec. 3, 1963, to elect the first chairman, the members of the first Borough Assembly, and the members of the first KPB School District board. Peninsula voters also would determine whether the borough would attain first-class or second-class status.

Harold Pomeroy, of Bear Cove (Kachemak Bay), was elected chairman. The choice of second-class borough was overwhelmingly selected, 2,037 votes to 252.

But, even after all the contentiousness concerning the seat of borough power, that issue remained unresolved.

The seeds of the answer, however, had perhaps already been sown. Most of the Study Group’s important meetings had been held in Soldotna because of its central location, and on Jan. 4, 1964 — three days after the borough was incorporated officially — the first meeting of the Kenai Peninsula Borough Assembly was held in Elks Hall (now the VFW building) in Soldotna.

The fight wasn’t even close to being over, but a barely visible line had been drawn in the sand.