A probate court met in Seward on Jan. 28, 1915, to determine the fate of the personal property of Cooper Landing-area resident King David Thurman, who had last been seen six months earlier and was presumed dead.

No body had yet been discovered, despite wide-ranging searches and investigations of Thurman’s usual haunts, but even Thurman’s friends and acquaintances doubted he could still be alive. Consequently, the U.S. commissioner in Seward appointed James Forrest Kalles — one of those friends and also a local resident — to be guardian of the Thurman estate, such as it was.

A miner and trapper with a home cabin on Bean Creek, near Cooper Landing, King Thurman owned at least one boat, numerous trapping and mining supplies (some homemade), and a faithful dog that was his companion on most of his outings.

The commissioner instructed Kalles to “collect all the personal property of the said King D. Thurman and to dispose of the same to the best advantage; to cash checks … and from the proceeds of the sale of said personal property to pay all legitimate debts … rendering a full account of his guardianship to this Court at the earliest opportunity.”

Furthermore, the commissioner ordered the Seward postmaster to direct to Kalles all mail meant for Thurman, “with a view of locating and ascertaining the whereabouts of the relatives, etc., of the said King D. Thurman.”

A month later, James Kalles learned the truth about the disappearance of his friend.

Earlier Days

Details concerning the childhood and young adulthood of King David Thurman (sometimes spelled Thurmond) have been thus far hard to come by.

He was born in the 1870s in rural Illinois — probably in 1878 but possibly as early as September 1876 — fourth in what eventually became a family with six kids. Their parents were farmers and children of the rural South: Harrison H. and Paralee (nee Davidson) Thurman, who had wed on Christmas day in McNairy County, Tennessee, in 1862.

By the time the 1900 U.S. Census was enumerated in Jefferson County, Illinois, King Thurman was no longer living at home, and census records of his whereabouts have yet to materialize.

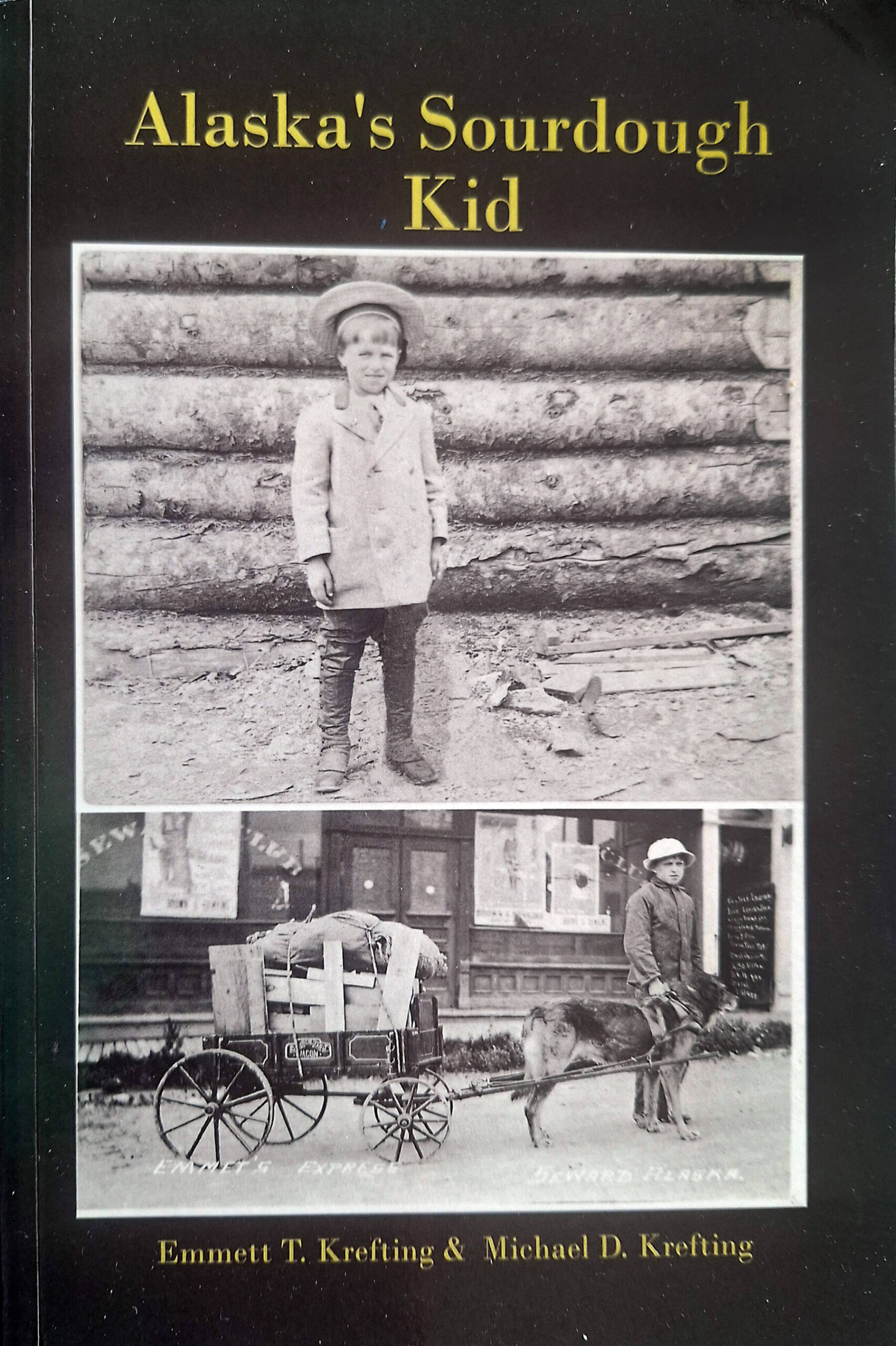

Emmett T. Krefting, who befriended Thurman in Alaska in 1907 and wrote about their friendship in the memoir Alaska’s Sourdough Kid, stated in Chapter 12 that “King Thurman never talked of the past.” However, in Chapter 14, he described Thurman philosophizing in general terms about parenting and wondered whether Thurman had really been talking obliquely about his own upbringing.

“Emmett,” said Thurman (according to Krefting, whose divorced mother at that time was beginning a relationship in another man), “it’s better to have no poppa than to have a bad poppa. And it’s better to have one good parent, like you got, than having two bad ones. Imma guessin’ your momma never gave you a real whuppin’ … and a kid knows the difference between a spankin’ and a beatin’.”

No evidence has yet been unearthed to demonstrate whether Thurman’s childhood was a difficult one. And the records concerning his siblings have not thus far lessened the uncertainty.

It appears that King’s elder brother Joseph joined the U.S. Army and died fighting in France during World War I. His eldest sister, Sarah, died of chronic nephritis, a kidney inflammation, at age 62 in 1932. Eldest brother Thomas lived to be 97; he had been married and had helped produce a passel of children.

Younger sister Martha lived only about 20 years, dying sometime after giving birth to a son in late April 1902; her widower husband remarried in 1905. Youngest sister, Nancy Jane (who went by “Jennie”) married in 1902 and was probably divorced before the United States entered World War I; her whereabouts after the divorce are unknown.

What does seem clear about the life of King David Thurman is that he arrived in Alaska during the turn-of-the-century gold rush. In Krefting’s memoir, he recalled a Canyon Creek mining camp foreman telling him that Thurman was “among the first to find gold here in the Hope-Sunrise district.” Gold was discovered near Hope and Sunrise in the late 1880s, prompting a rush that began in about 1896.

The Canyon Creek foreman, in 1907, also said that Thurman had previously worked for Simon “Sam” Wible, who had come to the Kenai Peninsula in 1898 to work a hydraulic-mining operation on Sixmile Creek and may have purchased his first Canyon Creek claim as early as 1899.

In 1902, the Daily Morning Alaskan (Skagway) reported that “King Thurmond,” of Dawson, was staying at the local Dewey Hotel.

Finally, when Thurman left Canyon Creek for a few days in 1907, he told Krefting that he needed to go check on one of his cabins, implying that he had at least two places in which to shelter while doing his mining and trapping, and therefore had been in the area for a number of years.

Training Days

When he first met King Thurman, Emmett Krefting was just six years old and living with his mother, the camp cook at Wible’s mining operation on Canyon Creek. Krefting’s mother had left Emmett’s policeman father and their home in San Francisco when Emmett was an infant. She had been making her way as a single parent ever since.

Thurman first appears in Krefting’s memoir in Chapter 11, entitled “A King Arrives.” He was allowed to stay in camp as a non-employee because of his prior working relationship with Wible, and he proffered his assistance around camp.

Krefting’s first impressions of Thurman were negative, however. “This was no king,” Krefting wrote. “He was a bum. His hat had holes, his shirt had holes, his pants had holes, and there seemed to be holes in his theory that he could in any way be of help….” He called Thurman a “motley creature” and a “contemptible gutterpup.”

But Thurman did help. With Wible’s blessing, Thurman planned to do some “sniping,” looking for gold in places already searched or disregarded as not worth investigating. With Krefting’s mother’s permission, he took young Emmett along, ambling with the boy down into the canyon and thus allowing the cook to focus more fully on her duties. Thurman also indicated that he and the boy would try to bring back something to add to the camp cookpot.

Krefting was initially skeptical of King Thurman’s expertise and abilities in such matters, but before long the unlikely duo had collected a small haul of nuggets and gold flakes, and Krefting’s opinion of his new companion began to transform. Suddenly, Thurman seemed like a “frontier sage,” wily and wise, despite his ragged appearance.

Thurman also taught Krefting some gold-mining subterfuge. He convinced the boy that they had to hide the true nature of their success from the other men in camp, using the two-poke system — one poke hidden and containing most of the gold, the other poke out in the open and containing only unimpressive fragments of the real haul.

Thurman encouraged Krefting to brag about the contents of the latter while concealing the former. In this way, the other men of camp came to believe that Thurman was little more than a glorified babysitter, not a man contributing what would become hundreds of dollars to the cook’s coffers (and to his own). Consequently, Thurman convinced Krefting and his mother, their small deceit made it less likely that anyone in camp would attempt to steal what they had worked for.

In addition to the gold they gathered, Thurman and Krefting attempted to return to camp each day with something hunted or foraged — dandelion blooms, spruce tips (for tea), ptarmigan or grouse, trout, berries and mushrooms, for example.

It was a magical time for the boy, and for his mother, who believed that the accumulation of gold could unlock future possibilities — well beyond what her meager cook’s income could produce — for herself and her son.

But their time with King Thurman was not without incident.