AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is Part Two of a two-part story about a physician/surgeon who came to Seward in the 1920s with some curious blank spots on his resume. In Part One, Reilly Jefferson Alcorn left the teaching profession in Montana under less than desirable circumstances and then punctuated his early medical career with an illegal abortion, a dead patient, a manslaughter conviction, and a seven-year prison sentence.

Although Dr. R. J. Alcorn spent only a few years in Alaska, he certainly got around.

In about 1925, Alcorn ventured to Alaska for the first time, being named surgeon for the Chichagof Mining Company, operating near Sitka. In April 1927, he was named the Alaska Railroad surgeon for the government hospital in Anchorage. In November of that same year, he helped open a hospital in Seward. He appears to have practiced briefly in Juneau in 1929, and acted as a cannery doctor in Seldovia for a while in 1930.

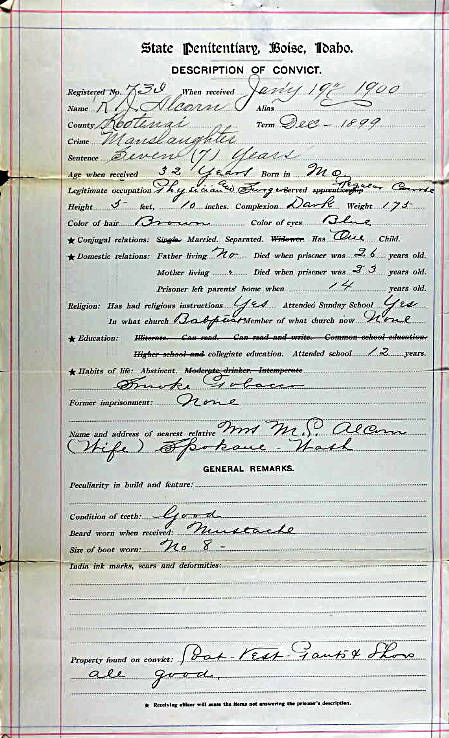

With few exceptions throughout his life, R. J. Alcorn stayed only briefly in any one place. But in 1900, he found himself confined in Boise, Idaho, as Convict #739 in the Idaho State Penitentiary.

His attempts to receive a pardon in 1900 and 1901 failed, but he succeeded in 1902. He was released on parole, restricted to living in only Idaho or Nez Perce counties, and required to make monthly reports on his employment and earnings. Any violation of these rules—or several others—would result in the immediate return to the realm of prison warden E. L. Ballard.

By the following year, the State of Idaho was requiring prospective doctors to pass a licensing exam, and in April 1903 Dr. Alcorn successfully passed the test. In January 1904, he received a full, unconditional pardon, his rights as a citizen were restored, and he was allowed to legally practice medicine again. Soon he had an office in Lewiston, Idaho.

The Drs. Alcorn soon moved to Stites, Idaho, where their daughter, Wilma Mae, was born in 1906, and where R. J. practiced medicine and sold drugs out of a small pharmacy. By 1910, they were living in Kooskia, Idaho, and had had a second son, who had died in infancy.

For the next few years they moved about Idaho, finding themselves in Wisconsin sometime in 1914. Then in April 1915, while living in Sturgeon Bay, R. J. applied for a license to practice medicine in Wisconsin. Despite omitting his manslaughter conviction—and despite two letters questioning his skills as a physician—he succeeded, becoming officially licensed on June 29.

In his application, he had glossed over the truth with general statements: “I began the practice of medicine in Idaho in 1898, before examination was required. Practiced one year. Gave up practice for four years … (and then practiced) in Idaho for 10 years from 1904-1914.”

He left out that he had been forbidden to practice for four years. He also omitted the fact that he had been practicing medicine in Idaho in 1896, two years before he had completed his medical degree.

In the application packet were five letters—three containing brief but hearty recommendations, the other two urging the Wisconsin Board of Medical Examiners to reject Alcorn’s application. One man from Ellison Bay, Wisconsin, blamed Alcorn, whom he called “unfit,” for the deepening of his brother’s poor health.

He wrote: “I emphatically protest against your honorable body granting this man a license to practice as I do not think he has the ability to do so … and if you wish me to give any more information bearing on the case I have cited, I am perfectly willing to do so.”

Various newspaper articles over the next 10 years illustrate that the Alcorns lived and practiced in Idaho, with a brief sojourn or two in Washington. In 1924, R. J. ran for coroner in Bonner County, Idaho. Yet, when he discussed his qualifications a few years later, he claimed he had practiced in Milwaukee for many years and spent eight years as a surgeon for the North Pacific Railway.

While it is certainly possible for newspaper reporters to get things wrong—perhaps mistaking being a surgeon in towns along the railway for being a surgeon for the railway company itself—it appears that Dr. Alcorn was once again blurring the lines of truth.

Of course, it must be said that Alcorn, according to numerous newspaper stories, also accomplished many good things as a medical professional. He opened hospitals. He mended broken bones. He traveled far to tend to ailing patients, including the many sick and dying during the influenza epidemic of 1918-19. And in 1919, he provided Idaho County with its first-ever x-ray machine.

But by about 1925 the Alcorns were on Chichagof Island in Southeast Alaska, and in 1927 Dr. R. J. Alcorn parlayed that experience into a temporary new job in Anchorage, replacing Dr. Arthur David Haverstock, an Army physician who would also go on to practice medicine in Seward about two years after the Alcorn family departed.

In Seward, the Drs. Alcorn saw a need to extend their hospital’s care beyond the Gateway City and prepared their facility to accept patients “from the Westward,” generally referring to Southwest Alaska. During summers, government ships with trained physicians and surgeons traveled the Alaska coastlines providing medical services, but from October to May residents of those areas had no ready access to medical care.

Unfortunately for the people of Seward and the Westward, the Alcorns could not sustain such services. Sometime after August 1928, their hospital closed its doors, and the Alcorns moved on. After stops in Seldovia and Juneau, they returned mostly to more familiar territory.

According to the 1930 U.S. Census, the Alcorns were residents of and physicians in Wenatchee, Washington. They also lived and practiced for several years in Sandpoint, Idaho, where R. J. ran successfully for coroner.

In the mid-1930s they were in Coulee, Washington, when R. J.’s health began to fail, and he traveled to a warmer, drier climate to recover. A three-line notice appeared in the Spokane Chronicle on Oct. 31, 1936: “Dr. R. J. Alcorn is seriously ill in California. Mrs. Alcorn left this week for his bedside.”

He died Feb. 18, 1937, in Los Angeles. He was 70 years old.

After a life almost constantly in motion, he was finally at rest.