Of the Kenai Peninsula School District’s approximately 8,900 students, three are blind. Jordana Engebretson, the district’s teacher for the visually impaired, said this is an unsurprising proportion.

“The reality is that 99 percent of the population is sighted,” said Engebretson, who is herself blind. “It’s a very, very low incidence (of blindness). From that little, an even smaller number is kids who are academic. … My hope and my desire has been that I can create an awareness that these kids are here.”

At Soldotna’s River City Academy, where Engebretson has her office, the only blind student is junior Maria Maes, who last Thursday helped Engebretson lead a Blindness Challenge that gave 22 River City middle- and high-schoolers the chance to experience the world without vision and to use the tools that help the blind through daily tasks such as writing, signing forms, and typing messages.

Of the 22 students who volunteered for the challenge, half were blindfolded. The others became their guides, leading them into the River City Academy library from the music room.

One blindfolded student, Kaegan Koski, said the walk had been a strange experience.

“You see these walls in front of you that could or might not be there,” Koski said. “But it’s almost as if there’s a shadow going over your eyes so that you think there’s a wall, but you force yourself to keep walking because you somewhat trust the guy who’s helping you. And then you feel like you’ve just walked through that wall. You’re just like, ‘Wow, I don’t have any clue anymore where I am.’”

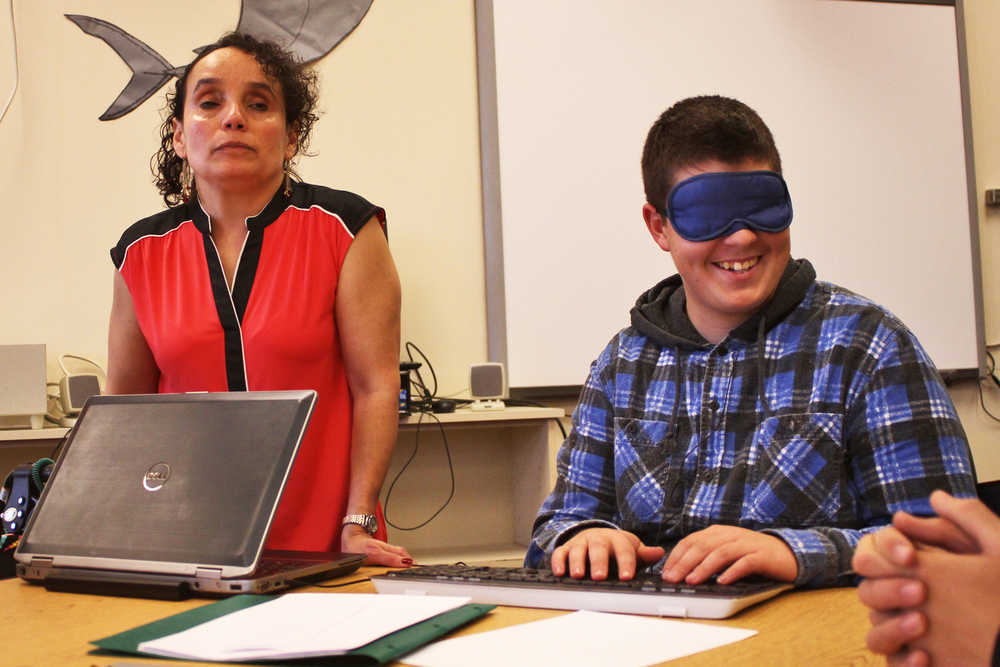

Three tables were set up in the library, with activities focused on the themes of art, texture recognition, and school. Students at the art table learned to draw with swell paper, which expands when marked by ink so that lines can be felt. At the finger recognition table, students tested their ability to identify shapes by feel and to memorize correlations between textures printed on plastic sheets and the unseen color of the sheet. At the school table they used equipment such as text-to-speech software and ruler-like writing guides that aid blind people in doing written work.

Maes said other students often see her wearing headphones to use a speaking computer, but the other tools such as swell paper and writing guides are likely less familiar. She hopes the curiosity stirred up by the challenge will continue.

“I’m making a conscious effort not to hide my struggles in life, including blindness and other things people have stigmas about,” Maes said. “I’m hoping this is the start of people asking ‘what is that?’”

Engebretson said the goal of raising awareness will benefit the district’s blind students even after they leave school.

“These kids are going to grow up here,” Engebretson said. “This is going to be the place where they live, the place they work if they don’t go away from here. So that’s the reason we do activities like this.”

She believes the education effort has had some success.

“We (the visually-impaired learning program) have been here 3 years, and I have seen a change in the student body,” Engebretson said. “From the first year we came here, when Maria was a freshman, to now that she’s a junior, the student body is way more accepting and aware of the difference.”

After the challenge in the library, it was lunch time. Most students took off their blindfolds and returned to the world of vision, but some made their way to River City’s gym/cafeteria with blindfolds on. Maes said the ones who remained blind through lunch would learn that “social situations are the hardest.”

“There’s a lot of sarcasm among middle-schoolers and high-schoolers,” Maes said. “When someone is sarcastic with me, I just stare blankly — because 90 percent, they say, is facial expression, and without that I won’t get it. A lot of jokes are lost on me because of that. I depend on tone, they depend on expression. … I hope that sinks in during lunch.”

Many of the blindfolded students in the gym/cafeteria carried on as they normally do. One, Calysa Saporito-Mills, took a photograph, locating her subjects by sound. After lunch Koski stood up and prepared to sprint blindfolded across the gym after his friends shouted that the way was clear (it was). In the end, though, he sat back down without making the run.

One pair of students — blindfolded Jenna Helminski and her sighted partner Capra Edwards-Smith — left the school to pick up lunch from Froso’s restaurant. Capra said Froso’s was busy, with a crowd of about 50. Most, he said, “were pretty aloof to the entire situation,” though one person held a door for the blindfolded Helminski.

Conversing blind, Helminski noticed the social effect Maes had spoken about, though she acknowledged a difference between her experience — having a visual memory of the correlations between voice, facial expression, and emotion — and that of Maes, who was born blind.

“A lot of conversation is looking at facial recognition,” Helminski said. “It’s definitely harder to read emotions and everything. … Body language is a huge thing, but I’m trying not to use body language to see what people are saying. You have to listen to what they’re saying, how they’re expressing it, rather than what their body shows. Like somebody frowning, but you can actually hear somebody frowning when they’re talking.”

Edwards-Smith said that being Helminski’s sighted guide through the school and the restaurant had also made him see things differently.

“One thing was just how three dimensional the world is,” Edwards-Smith said. “As someone who’s sighted you have to call out all the little differences you usually take for granted, like a small step or a tiny pothole. All those things have to be taken into account.”

“Yeah,” Helminski added, “I stumbled down stairs sometimes that were probably about three inches. When you can’t see it, it feels like a foot and a half.”

Helminski said her few hours of blindness had been an instructive experience, concluding that “it takes a lot more focus to be blind than it does to see.”

“Oddly enough to say, it was really big eye-opener on how much I actually use my sight to get around and do anything,” she said.

Reach Ben Boettger at ben.boettger@peninsulaclarion.com.