The internment of more than 100,000 Japanese-Americans in the United States under Order 9066 is well-known as an abhorrent act that the American government has since apologized and made reparations for.

What’s less known in Alaska is where some of those people went after they were released from internment camps in the Lower 48.

“We decided to tell this story not just what happened to them during the war, but what they did before the war and after the war,” said archaeologist Morgan Blanchard in a phone interview.

A National Park Service funds-matching grant to the Alaska chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League will help the organization investigate archives and seek out family members of those Japanese-Americans in Alaska who were interned for the length of the war, the JACL said in a news release.

“This is the first chapterwide effort. There was some effort to document history, but more of individual history,” said Suzanne Ishii-Regan, co-treasurer of the Alaska chapter of the JACL. “We’re grateful for the grant because hopefully it’ll let us get this information published. It’s exciting; it’s a little intimidating.”

In Juneau, the Empty Chair Project has done good work to recognize what happened in the Southeast, Ishii-Regan said. The JACL will carry on the work, as it seeks to find what happened to all of those interned across the state.

Origins

The roots of the project came from the discovery by Blanchard of a holding camp at Joint Base Richardson-Elmendorf for those incarcerated for being of specific national origins.

“This kind of came out of a project I started a number of years ago where I discovered where the Fort Richardson Internment Camp was,” Blanchard said. “Along the way, we found the list that gave us the names of everyone that was interned as a foreign national here in Alaska.”

The Air Force readily supported the project, aiding further research into what had happened, Blanchard said. According to records recovered by Blanchard, 104 Japanese-Americans were arrested in Alaska, as well as 18 German-Americans and five Italian-Americans.

“When the war started — or even before the war — the government made a list of people to arrest. They started arresting people on Dec. 7, 1941,” Blanchard said. “When they got arrested, they had wives and kids. The kids were American citizens. Some of the wives were American citizens.”

Half of the German-Americans and all but one Italian-American were released, Blanchard said, but none of the Japanese-American detainees were released.

“You had to go before a tribunal, and they would make a determination if you were a dangerous enemy alien,” Blanchard said.

Those incarcerated stayed at Richardson for a relatively short period of time before being transferred to camps in the Lower 48, Blanchard said. Very little information about the Fort Richardson camp exists, Blanchard said. Much of it was destroyed by a fire that destroyed many WWII records.

“There are some instances in which the second generation — young men — who were already enlisted had to guard their fathers,” Ishii-Regan said.

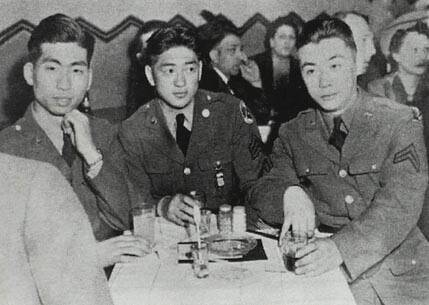

Many young Japanese-Americans eventually enlisted, even as their families were in internment camps in the United States.

“A number of the sons of these guys ended up in the 442nd (Regimental Combat Team),” Blanchard said. “Despite the treatment, a number of them did end up in the war.”

The Army’s 442nd RCT was a segregated Japanese-American regiment, known for being the most decorated unit of its size in American history, according to the WWII Museum. The 442nd served with distinction in the European theater of the war.

After the war ended the internment camps were closed. Many Japanese-Americans returned to Alaska, but others went elsewhere, some even returning to Japan, Ishii-Regan said. Now, the project will attempt to pick up some of those threads.

Following the pattern

“We’re trying to do oral history interviews with descendants. To the best of our knowledge, everyone who was interned is dead,” Blanchard said. “They’re delicate subjects. We’re talking about what the government did to people during wartime.”

The project will attempt to find out what happened to those interned through a number of methods, Blanchard said, including using the Freedom of Information Act with the FBI, digging through whatever archives can be found, and reaching out to family of those interned to collect their stories that have gone untold.

“A lot of our relatives didn’t want to talk about it,” Ishii-Regan said. “Even if you came back a decorated combat veteran, they still faced racism.”

The JACL is also looking for volunteers to help research the subject.

“It appears to us that more than a third of the first-generation men were married into Alaska Native families. They lived in the outlying areas,” Ishii-Regan said. “Many of them were significant contributing members of their communities.”

The grant is funds-matching, Ishii-Regan said, which means the JACL is looking to raise $15,000 to meet the $30,000 grant from the NPS. It’ll allow for more effective research into the past.

“It provides some money to pay for archival research because it doesn’t come free. We were hoping to be able to do a lot more in-person interviews,” Blanchard said. “Some of the goals that are supposed to come out of this, is, we’d like to write a small history of what happened in the state and what happened to the people who were interred.”

To contact the JACL either with information about the interned or to inquire about volunteering, email them at jaclalaska@yahoo.com.

Contact reporter Michael S. Lockett at 757-621-1197 or mlockett@juneauempire.com.