By Mark Thiessen

Associated Press

SEWARD — In the cold, choppy waters of Alaska’s Resurrection Bay, all eyes were on the gray water, looking for one thing only.

It wasn’t a spout from humpback whales that power through this scenic fjord, or a sea otter lazing on its back, munching a king crab.

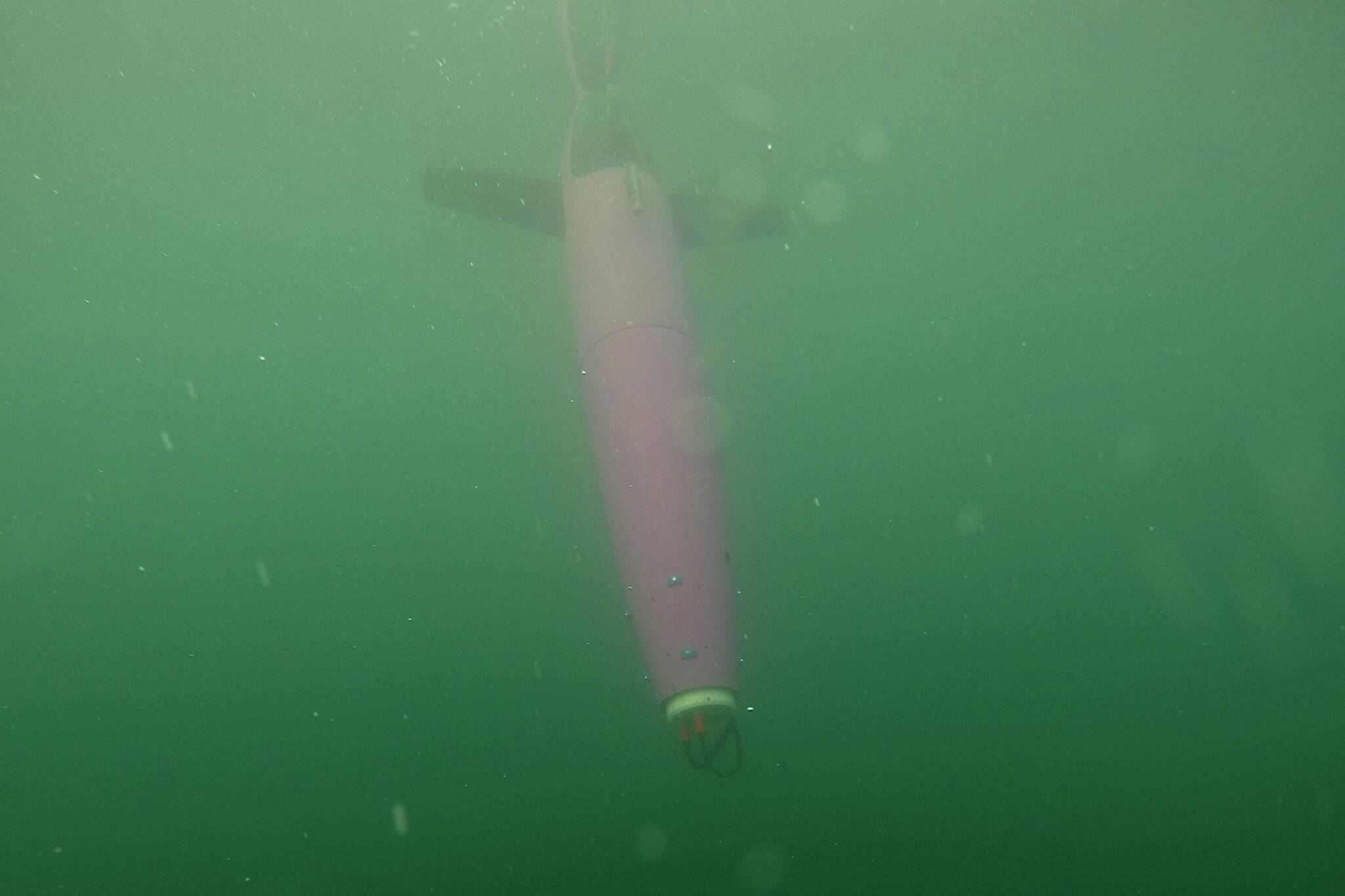

Instead, everyone aboard the Nanuq, a University of Alaska Fairbanks research vessel, was looking where a 5-foot long, bright pink underwater sea glider surfaced.

The glider — believed to be the first configured with a large sensor to measure carbon dioxide levels in the ocean — had just completed its first overnight mission.

Designed to dive 3,281 feet and roam remote parts of the ocean, the autonomous vehicle was deployed in the Gulf of Alaska this spring to provide a deeper understanding of the ocean’s chemistry in the era of climate change. The research could be a major step forward in ocean greenhouse gas monitoring, because until now, measuring CO2 concentrations — a quantifier of ocean acidification — was mostly done from ships, buoys and moorings tethered to the ocean floor.

“Ocean acidification is a process by which humans are emitting carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through their activities of burning fossil fuels and changing land use,” said Andrew McDonnell, an oceanographer with the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at the University of Alaska Fairbanks

Oceans have done humans a huge favor by taking in some of the C02. Otherwise, there would be much more in the atmosphere, trapping the sun’s heat and warming the Earth.

“But the problem is now that the ocean is changing its chemistry because of this uptake,” said Claudine Hauri, an oceanographer with the International Arctic Research Center at the university.

The enormous amount of data collected is being used to study ocean acidification that can harm and kill certain marine life.

Rising acidity of the oceans is affecting some marine organisms that build shells. This process could kill or make an organism more susceptible to predators.

Over several weeks this spring, Hauri and McDonnell, who are married, worked with engineers from Cyprus Subsea Consulting and Services, which provided the underwater glider, and 4H-Jena, a German company that provided the sensor inserted into the drone.

Most days, researchers took the glider farther and farther into Resurrection Bay from the coastal community of Seward to conduct tests.

After its first nighttime mission, a crew member spotted it bobbing in the water, and the Nanuq — the Inupiat word for polar bear — backed up to let people pull the 130-pound glider onto the ship. Then the sensor was removed from the drone and rushed into the ship’s cabin to upload its data.

Think of the foot-tall sensor with a diameter of 6 inches as a laboratory in a tube, with pumps, valves and membranes moving to separate the gas from seawater. It analyzes CO2 and it logs and stores the data inside a temperature-controlled system. Many of these sensor components use battery power.

Since it’s the industry standard, the sensor is the same as found on any ship or lab working with CO2 measurements.

Hauri said using this was “a huge step to be able to accommodate such a big and power hungry sensor, so that’s special about this project.”

“I think she is one of the first persons to actually utilize (gliders) to measure CO2 directly, so that’s very, very exciting,” said Richard Feely, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s senior scientist at the agency’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle. He said Hauri was a graduate student in 2007 when she accompanied him on the first acidification cruise he ever led.

The challenge, Feely said, is to make the measurements on a glider with the same degree of accuracy and precision as tests on board ships.

“We need to get confidence in our measurements and confidence in our models if we are going to make important scientific statements about how the oceans are changing over time and how it’s going to impact our important economic systems that are dependent on the food from the sea,” he said, noting that acidification impacts are already seen in the Pacific Northwest on oysters, Dungeness crabs and other species.

Researchers in Canada had previously attached a smaller, prototype CO2 sensor to an underwater drone in the Labrador Sea but found it did not yet meet the targets for ocean acidification observations.

“The tests showed that the glider sensor worked in a remote-harsh environment but needed more development,” Nicolai von Oppeln-Bronikowski, the Glider Program Manager with the Ocean Frontier Institute at Memorial University of Newfoundland, said in an email.

The two teams are “just using two different types of sensors to solve the same issue, and it’s always good to have two different options,” Hauri said.

There is no GPS unit inside the underwater autonomous drone. Instead, after being programmed, it heads out on its own to cruise the ocean according to the navigation directions — knowing how far to go down in the water column, when to sample, and when to surface and send a locator signal so it can be retrieved.

As the drone tests were underway, the U.S. research vessel Sikuliaq, owned by the National Science Foundation and operated by the university, conducted its own two-week mission in the gulf to take carbon and pH samples as part of ongoing work each spring, summer and fall.

Those methods are limited to collecting samples from a fixed point while the glider will be able to roam all over the ocean and provide researchers with a wealth of data on the ocean’s chemical makeup.

The vision is to one day have a fleet of robotic gliders operating in oceans across the globe, providing a real-time glimpse of current conditions and a way to better predict the future.

“We can … understand much more about what’s going on in the ocean than we have been before,” McDonnell said.