AUTHOR’S NOTE: Place names can be ephemeral. And they can fade for myriad reasons. Sometimes offensive names are replaced by more appropriate appellations, as in the case of Dillingham’s Squaw Creek recently being given the Yup’ik name Amau Creek. Sometimes names disappear, such as when the planned community of Gruening, named for Alaska’s U.S. Senator Ernest Gruening, was a Nikiski-area dream that never quite came true. This is the story of Riddiford, which was the name of the community at the outlet at Kenai Lake — until it suddenly no longer was.

The small settlement at the Kenai Lake outlet was known initially as a stopping point for those people traveling down the lake and then downstream for mining, hunting or fishing purposes. It was established by a miner and entrepreneur named Joseph M. Cooper, who apparently also established a trading post, the first permanent structure, at that location in the late 1880s. Cooper Lake, Cooper Creek, Cooper Mountain and Cooper Landing were all named for Joseph Cooper, who died in 1899.

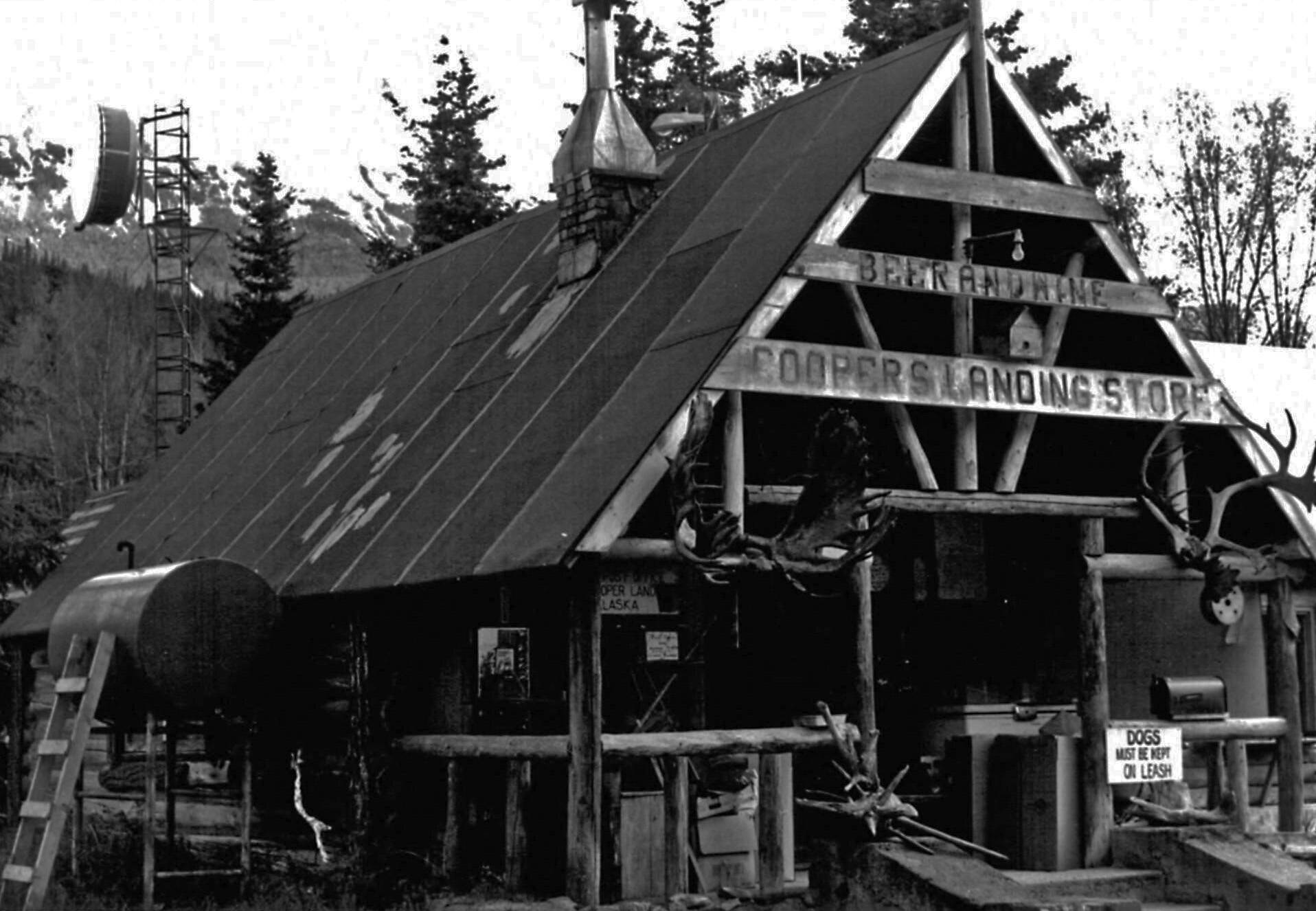

The area early on was known as Cooper’s Landing, mainly for the landing itself since few people actually lived there — certainly not enough residents to qualify as a town. By 1914, it was generally known as Cooper Creek Landing and, while growing in population, was a full decade away from having its own post office.

Some of the earliest permanent settlers at the landing were Frank Towle, Lou Bell and Jack and Charles Lean, and their families.

When the first post office did open in 1924, however, it was not named for Joseph Cooper or for any of these early settlers. It was named Riddiford. And when the first school opened in 1929, it, too, was named Riddiford.

Decades later, some people speculated that Riddiford had been an early prospector. Others asked, though, asked why the name of some forgotten prospector would supplant Cooper’s, an earlier and arguably the most noted figure from the area and a man whose name was already firmly attached to its history and its geography.

Historian Craig Mishler, while crafting a nomination form in 1984 for the Cooper Landing historic district’s inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places, wrote that the post office and school had been named after “a man who donated his land for a post office.” History blogger Ray Bonnell, in 2022, echoed that belief.

Perhaps the “early prospector” and the “man who donated his land” had been one and the same.

While evidence to the contrary was sketchy, evidence in support of this idea seemed to rely on hearsay and broad assumptions. After all, the Riddiford Post Office had been abandoned in 1928, and the next postal iteration in the area (in 1937) had been dubbed the Cooper Landing Post Office. That post office closed after only two years, but when it reopened in 1947, “Cooper Landing” was again the name. “Riddiford” was no more.

Likewise, low enrollment prompted the Territorial Board of Education at the end of 1935 to close the Riddiford School. When a new facility finally opened in its place in 1952, it was named the Cooper Landing School. Again, no Riddiford.

Lois Allen’s 1946 book, “Alaska’s Kenai Peninsula,” contained a section on Cooper Landing but made no mention of Riddiford. As subsequent decades passed and histories were written, the Riddiford name mostly faded from the record or became little more than a footnote.

So who was this Riddiford, and why did this name hold such sway at the site of Joseph Cooper’s boat landing for more than a decade?

Finding Riddiford

At some point during her 30-year tenure as postmaster for Cooper Landing, Betty Fuller told local historian Mona Painter that she’d heard Riddiford had been some sort of post office official. Painter wasn’t sure, but she included this idea in the Cooper Landing chapter of the 1983 book “A Larger History of the Kenai Peninsula.”

As it turns out, Fuller was correct. The post office in the town she served for three decades had, indeed, been named for a longtime postal employee. He was Charles Arthur Riddiford, a man who had never lived in Alaska.

Alaskan places had been named for outsiders before. The highest mountain peak in North America was named for U.S. President William McKinley before it was formally renamed Denali. The city of Utqiagvik was for decades known as Barrow, after a geographer in the British Admiralty; the town of Whittier was named for an East Coast poet; the city of Fairbanks for a U.S. senator from Indiana; the community of Teller for a U.S. senator from Colorado who had helped establish a reindeer station in the area.

The Seward Peninsula, as well as the town of Seward itself, were also named for a bureaucrat, William Henry Seward, but he, as U.S. Secretary of State, had negotiated with the Russians for the American purchase of Alaska. That connection, at least, seemed logical.

But why would a postal employee merit being the namesake for a remote community in Alaska?

Charles Riddiford worked for the United States Postal Service for more than four decades, rising quickly to the rank of postal inspector. During the peak of his career, he was one of the most famous postal employees in the entire country. His jurisdiction at one point covered what was then called the Northwest District, which encompassed all of Washington, Oregon, Idaho, Montana and the Territory of Alaska.

Riddiford was born in Birmingham, England, in 1867. By age 21, he had emigrated to the United States. Two years later he was married to Jessie M. Edwards, living in Spokane, Washington, and had filed the paperwork to begin his naturalization process.

Over most of the next decade, Riddiford worked various jobs on his path to USPS employment. He was a grocer, then a deputy county auditor and an accountant — until 1897, when he landed a job as a USPS utility clerk in Spokane. A staff photo from 1898 shows a lean, mustachioed Riddiford, standing in his dark suit at one end of the back row.

He was a money-order clerk by 1900 and became a postal inspector by 1904, when he began a series of appointments outside of Washington state and started establishing an identity for himself as a top-notch, insightful and relentless investigator.

Over the next 15 years, he served as an inspector in Denver, San Francisco and Atlanta. Between these appointments, and after them, he and his wife and their two daughters returned to Spokane.

During these various appointments, his investigative exploits began making headlines. Wherever the crimes and the criminals led him, Riddiford and his fellow inspectors followed, and his reputation for success grew. Whether the misdeeds involved private citizens or members of the postal service itself, the criminals he pursued came to fear the prospect of having Riddiford on their trail.

In 1908, he questioned three suspects in Los Angeles who were accused of infiltrating a safe in a post office in Las Vegas. In 1915, he assisted San Francisco authorities in wringing a confession from a postal clerk who had stolen thousands of dollars from a post office in Wallace, Idaho, then moved to Palo Alto, California, and hid the money in his cellar, in a bottle submerged in the ashes of his hearth, and in a tin bucket buried in a corner of his chicken coop.

In 1920, Riddiford helped with a manhunt that led him from Atlanta to Texas when a suspect in a mail-fraud case was captured in Michigan, escaped custody by leaping from a rapidly moving train 100 feet into a small lake in the Tennessee mountains and, until his recapture, hid out as the operator of a gas station in Garland, Texas.

When the inspector returned to live permanently in Washington in 1921, the Atlanta Journal remarked, “Mr. Riddiford has made a brilliant record while in charge of the Atlanta office, and has been instrumental in bringing to justice a number of violators of the federal postal laws.”

But Riddiford’s fame would soon rise to even greater heights, and his connection to Alaska was just beginning.