AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the summer of 1899, with the expedition over for most of the members of the Kings County Mining Company, Brooklynite Mary L. Penney had a decision to make. She’d signed up for a two-year gold-mining adventure in the Klondike but had ended up stuck in the wilds of the Kenai Peninsula. Should she stay and try to get rich or accept defeat and head home? The difficulty of her decision is unknown, but the results are a matter of record.

On Sept. 5, 1899, this subtly sarcastic, double-decker headline appeared in the Brooklyn Daily Times: “RETURNING FROM THE KLONDIKE: Mrs. Penney Is Probably Rich in Experience Anyway.”

The subtext seemed clear enough: Mary L. Penney, like most of the other members of the Kings County Mining Company, was coming home to Brooklyn from a mining expedition to the north country, with nothing gained from her efforts, except, perhaps, a story to tell.

Although the newspaper left unclear Penney’s expected arrival date and her location at the time of publication, it is likely that she had recently arrived stateside and had telegraphed her husband William and her children that she would soon be boarding an east-bound train from the West Coast. She was probably chugging down the tracks when readers of the Times opened their newspapers.

The error-filled article said that William’s first letter from Mary in Alaska had been postmarked in Kodiak in October. After that, the three-masted bark Agate, bearing nearly 60 members of the mining company, had entered Cook Inlet and a relative silencing of communication with family and friends on the other side of the continent.

The newspaper appeared to examine the pending William-and-Mary reunion with a greater sense of humor than of wonder. It noted that both of the Penneys had learned valuable lessons from Mary’s adventure: “Mr. Penney knows more now than ever about the care of a family, and his wife will undoubtedly be able to furnish a novelist with all that is required to make the yellowest kind of a yellow story about her experiences in going around the Horn in mid-winter and in prospecting for gold in the Arctic El Dorado.”

In the many months of Mary’s absence, said the paper, “whenever Mr. Penney was asked concerning his wife, he expressed himself very sanguine that she would not come back until she at least had her share of gold. The woman was a stockholder in a prospecting, mining and trading company and (had) invested $500 in cash to become a member.”

Despite Mary’s dreams and the newspaper’s low-brow assessment of her experience, the culmination of her journey was decidedly anti-climactic. Her daughter Geraldine would later tell her own daughter, Audrey, that Mary arrived home “thin, somewhat unkempt, with her hair in two pigtails, her (money) gone, and a little chamois bag of gold nuggets to show for her valiant venture.”

“Thin and disheveled she was,” wrote Audrey in a narrative about her grandmother, “but not disillusioned. ‘I’ll make money yet with my nursing (career),’ she told Grandpa.” Mary hoped to keep traveling and keep having adventures. She was about 40 years old and determined to not stop moving, despite having five children ranging in age from 12 to 21.

She also knew that William, now nearly 67 years old and preferring to remain in Brooklyn as much as possible, would be an unlikely companion on any far-flung escapade she might undertake.

Choices to make

Not every member of the Kings County Mining Company chose to leave Alaska when Mary did. In fact, although most of the miners departed during that summer of 1899, a handful of them never left. Another handful departed briefly and then returned. At least one of them died before he ever had a chance to leave.

In fact, William Barber Hurd was dead only about two weeks after Mary Penney’s pending homecoming was announced by the newspaper.

Eugene R. Bogart, the Alaska Commercial Company’s station agent in Kenai, addressed the situation in a Sept. 26 letter to his superiors: “Had a serious accident here the past week.” Hurd, whom he referred to as “a brother Mason” from St. Lawrence County, N.Y., had “shot himself accidentally and was brought here and died while undergoing an operation of the arm.”

“Gangrene had set in and the arm was mortifying,” Bogart continued, “and Dr. Schneider (another member of the mining company) thought he would try and save him by operating, but the shock was too severe — and he died just as (the doctor) finished amputating.”

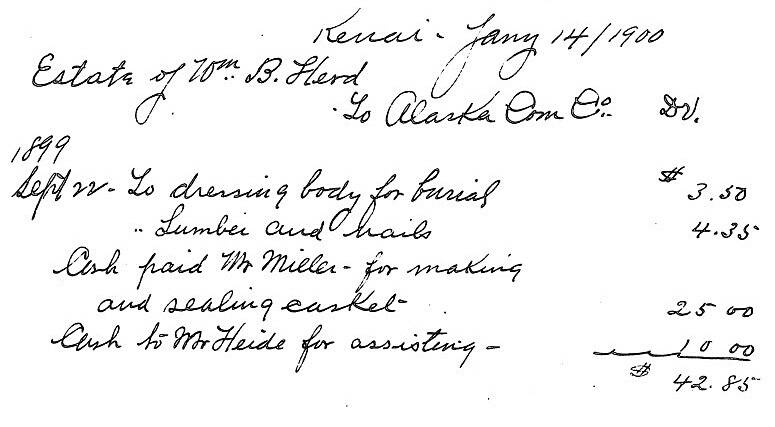

In a business-like manner, Bogart had the body “hermetically sealed” and buried in a wooden casket. He then notified relatives, Hurd’s Masonic Lodge back home and Bogart’s own bosses. He had used company funds to take care of the body. The bill for body preparation, lumber and nails, construction and sealing of the casket, and the burial, had come to $42.85.

The death was an awful conclusion to an awful final decade for 32-year-old William Hurd. His 59-year-old father had died in 1889. His 65-year-old mother had died in 1896, just days before William’s marriage to Mamie Harkin. Their son, William Anthony Hurd, was born in 1897, but Mamie died in February 1898, the same month Hurd left for Alaska. Then came an unfortunate coda: Hurd’s son, whom he never saw again, died at age 6 from carbon-monoxide poisoning from a gas leak in his maternal grandfather’s home.

Many other mining company members who remained behind were far more fortunate than Hurd, who is often considered the company’s only casualty.

Dr. Frederick Schneider, who had amputated Hurd’s arm in the vain attempt to save his life, was only 27 years old when he co-signed the invoice in Kenai for Hurd’s burial. He remained in Alaska until at least late in 1900. Determined to at least try mining for gold, he made his way to Sunrise, where he was counted in the 1900 U.S. Census. Later that same year, according to a newsletter from the Kodiak Baptist Orphanage, Schneider was on hand to provide medical assistance during an influenza outbreak there before returning home to Brooklyn.

Schneider appears to have remained single and in New York for the remainder of his life. He lived with a housekeeper in Brooklyn through at least 1930. He does not appear to have been counted in the U.S. Census for 1940.

Back in the summer of 1899, before the death of William B. Hurd, Schneider had been busy at work helping ailing Kings County members at the Skilak Lake site where the company had set up camp during the previous winter after struggling through the mountains from Kachemak Bay. Many of the miners were apparently suffering from scurvy, but company mining engineer H.C. Burbank was also being ravaged by what Schneider had diagnosed as Bright’s disease.

Bright’s, known today as nephritis, is a kidney disease that can be caused by factors such as injuries, infections and auto-immune diseases.

In July 2 and July 8 letters to superiors, Bogart said Burbank “came out (of the Skilak area) very ill” and was sent to Tyonek so he could catch the steamship Dora to Seattle. “I understand since he was taken over that there was no hopes of his living over that night,” wrote Bogart.

Whether Burbank survived is currently unknown. He has thus far proven difficult to track historically, especially since only his first and middle initials were used in newspaper accounts of the time. There was a Hanley Clement Burbank, who was born in 1858 and died in 1918 of Bright’s disease, but he appears to have spent most of his life in Iowa and Nebraska and has no clear connection to Brooklyn, mining or Alaska.

Besides Dr. Schneider, there appear to have been at least seven other members of the Kings County Mining Company who stayed in Alaska for an appreciable time after the rest of the company departed in 1899. Nathan A. Turner probably remained for five years, except to attend his sister’s wedding in New York. Herman Stelter stayed until illness forced his exit in 1917. Emile About moved to Nome to mine for gold and died there in 1916.

Thomas Weatherell returned east for two years and then went mining in Nome and other Alaska locations; he stayed in Alaska until the late 1930s. In 1900, three of the company members — Carl August Petterson, Eric Hellman and Alfred Johnson — were all living together in Kenai.

Hellman eventually moved to Washington and then British Columbia. Johnson’s further story is unknown. And Carl Petterson mined and fished commercially until he became a Kenai merchant. In 1903, he married a Kenai woman, raised a family and lived there for the rest of his life.