AUTHOR’S NOTE: After many years of making do with an absence of an official local burial ground, some citizens of Homer, in 1928, created a community cemetery. The day after the site was selected, the cemetery’s first occupant — Karl Albertson, the victim of a hunting accident — was brought home for interment.

For about a half-dozen years, from 1928 until the mid-1930s, the Homer Community Cemetery served its purpose without a hitch.

The cemetery’s second occupant was interred in 1929. She was Bonnie Bowers, infant daughter of Phina and Glen Bowers.

Three more bodies were added in 1932: Ada K. Anderson, wife of Ed Anderson; and Oscar Munson’s wife, Nellie, and their infant daughter, Helena Luderina.

A sixth interment occurred in 1933 when William Nielsen “was killed on a boat,” according to longtime Homer resident Margaret Anderson.

In 1934, Alfred Anderson lost his wife, Marion, and their two daughters (two-year-old Elizabeth and three-month-old Aileen), when they drowned attempting to land a boat in Beluga Slough during a strong windstorm. Accounts of this tragedy vary considerably, but Alfred, who had been on hand to greet his family returning from Seldovia, was powerless to save any of them.

Cemetery residency had climbed to nine.

Then problems arose with Section 16, the public-schools land containing the cemetery.

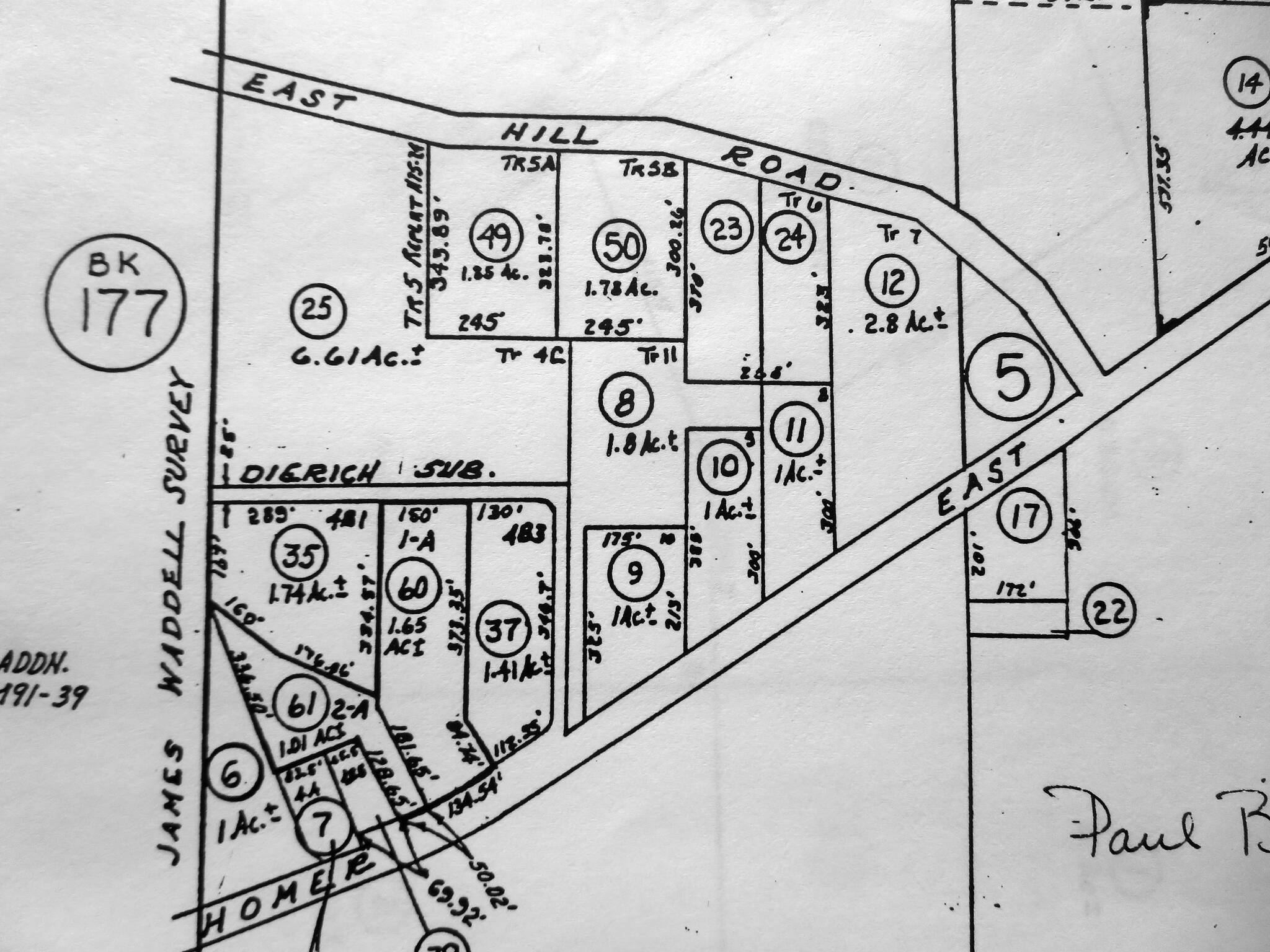

Arleen Kranich, in a Sept. 3, 1959, letter to Alaska attorney general John Rader, explained what happened, starting in about 1934: Section 16 “was thrown open for homestead[ing] and exchanged for another section farther north. James Waddell filed on a part of the section containing the cemetery, without declaring it, and during the next few years proved up on the land without declaring the cemetery.”

Without declaring the land officially, Jim Waddell was, in essence, denying its existence.

Waddell, according to Kranich, then moved his house behind the cemetery and began using the cemetery’s driveway as access to his home. He told the cemetery’s originators that he would soon create his own separate driveway and cease traveling through the graveyard. He still had not done so by 1946, when he sold his home to Jack Mills.

Before that sale, however, burials continued and a few changes to the cemetery took place. In 1936, Betty S. Bernard, daughter of Nils Svedlund, was interred. The next year, five more bodies were added: Tom Caughlin, Caroline Anderson and an unnamed Anderson infant, Ero Walli and Cyrus William “C.W.” Harrington.

Around this same time, with the blessing and assistance of Waddell, Homer residents ditched along the cemetery’s north side in an effort to stop ground water from seeping into the graves.

In 1939, Vern Latta became the final Homer resident — and the 16th overall — to be buried in the community cemetery prior to the 1940s, when about a dozen more would be added.

When Jack Mills took up residence in Jim Waddell’s former home, he continued to drive there through the cemetery— “in fact,” said Arleen Kranich, “almost over one of the graves.”

In an attempt to provide security for the cemetery, and perhaps to bring closure to the driveway issue, members of the local American Legion bought fencing and metal posts to enclose the property.

“However,” wrote Kranich, “when they put up the fence across the driveway … [Mills] became very angry and tore the fence down, as he said the old driveway of the cemetery was his.”

Kranich traveled to the Land Office in Anchorage to discuss the problem. Officials there told her that Waddell should have declared the existence of the cemetery when he first filed for a homestead and also when he proved up on the property. Since he evidently had failed to do so, he could, they said, be in danger of forfeiting his entire claim.

“I did not want to create troubles for Mr. Waddell,” Kranich wrote, “so I told them that I felt sure he would clear it all up.”

Unfortunately for the clearing-up effort, Waddell and his family moved out of the area around this time.

More time passed without anyone contacting him, and, said Kranich, “the next we heard was that [Waddell] had sold that part of his property, including the cemetery, to Mr. [Clarence] A. Nelson, of Homer. Nelson later began charging people $75 apiece for burial plots.

Eventually, Waddell claimed that community members should have pressured him into deeding the property to them. The community, on the other hand, believed all along that the land had been properly filed upon back in 1928. They assumed Waddell knew this and should have relinquished his claim.

Meanwhile, in 1951 up on the Homer hillside, on Thomas “Jiggs” Tice’s property north of Diamond Ridge Road, a further complication arose.

Tice’s friend, veteran pilot Glen H. “Tex” Hickerson, long an admirer of the views from Tice’s property, died in an airplane crash near Seldovia. To honor his friend, Tice arranged for the interment of Hickerson’s body on his place and later transferred the operation and maintenance of this new cemetery ground to the local American Legion.

For a few years, the site was known as the General Buckner Post 16 American Legion Cemetery. Receipts for gravesite purchases were signed by cemetery chairman Sam Pratt. A plot in the new cemetery cost only $20 by 1958.

The following summer, the new cemetery — much larger than the community site on East End Road and now dubbed Hickerson Memorial — was surveyed by Henning Johnson.

People were dying to get in — sometimes, as in the case of Hickerson himself, in tragic ways. Of the first nine Hickerson cemetery occupants, more than a third died violent deaths, including a nurse’s aide who shot herself, a construction worker struck by an out-of-control fighter jet, and a man killed when a bullet fired at a bull moose by the man’s son-in-law ricocheted off the animal’s antlers.

In 1959, Kranich closed her letter to the attorney general with a plea for help and these details about the continuing saga of the Homer Community Cemetery:

“We are very, very anxious to get this cleared up as the land is again listed for sale, and the people who have bought the land [adjacent] to the graves walk across the graves and use it for parking cars. Another driveway has been fixed up across the other side of it, and the trees have all been trimmed. It is very much in need of care.”

In the end, both cemeteries wound up under city ownership.

On April 27, 1966 — 38 years after it was founded for the good of the community — ownership of the Homer Community Cemetery was transferred from Clarence A. and Mildred B. Nelson, via quitclaim deed, to the City of Homer. It is unclear whether the cemetery boundaries had shrunk over the years — or earlier estimations of its dimensions had been incorrect — but its size upon the transfer to the city was about 0.28 acres.

On Jan. 22, 1969, a warranty deed transferred the roughly 3.4-acre Hickerson Memorial Cemetery from the American Legion into city hands.

Both properties have been managed by the city ever since.

On Feb. 3, 1984, Homer city clerk Kathy Richardson and public works director Whitey Morgan issued a memorandum that opened this way: “Homer Community Cemetery is for all general purposes a closed cemetery. There are less than twenty plots available, and they have been identified as reserved for old timers or spouses of those already interred there.”

Around this same time, Margaret Anderson, of Homer, undertook the task of attempting to identify all of the burial sites within the cemetery, a task made difficult because so many grave markers had disintegrated, and the ground in some cases had settled. Record-keeping in the early days had been inconsistent.

Of the more than 80 graves then within cemetery grounds, Anderson positively identified all but nine. Furthermore, she and other concerned citizens arranged for the installation of a bronze memorial plaque to commemorate all those interred. A secondary plaque was added in subsequent years to record new arrivals.

The latest person to be buried in Homer Community Cemetery—91-year-old Robert John Walli, who died in 2016—was related to one of the earliest, his father, Ero J. Walli, who died in 1937.