By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

AUTHOR’S NOTE: This is second part of a two-part story about the early development of mail delivery in Kenai. Part One discussed Kenai’s first two postmasters, the challenges of getting winter mail from Homer, and the shift to a winter route through Seward after 1910.

In 1918, in order to protect Alaska’s mail carriers, their dogs and their cargo, the Territorial Legislature appropriated $20,000 for shelter cabins along winter trails throughout Alaska. As usual, the improvements on the Kenai Peninsula did not come quickly.

Although there were private cabins on parts of the winter route — including a trapper’s cabin along the Moose River and the Philip Wilson cabin below the Moose’s confluence with the Kenai River — no government shelter cabins would be completed for about five years.

One big improvement, though, happened much sooner.

In 1920, Anchorage contractor R. L. Stock oversaw the construction of a bridge spanning the Kenai River at Schooner Bend, 6 miles downstream from Cooper Landing. The bridge allowed Kenai-bound mail carriers to travel a light-duty wagon road along the south bank of the river before crossing the bridge back to the north side.

To reach the wagon road, however, carriers arriving from Moose Pass had to cross lower Kenai Lake near the mouth of Quartz Creek — either by mushing across the ice when the winter was cold enough or by loading their sled and dogs into a boat when the ice was unsafe.

Once mail carriers crossed the Schooner Bend bridge to the north bank, they followed the river downstream until it cut south toward Skilak Lake. The carriers kept a westward heading, across Jean Lake, up a low pass near Upper Jean Lake, and across the frozen swamps and lakes toward Kenai.

In March 1923, the Alaska Road Commission sent its acting superintendent, Walter W. Lukens, to perform a reconnaissance of the winter mail route. Over the course of 15 days, Lukens mapped the route and issued a report. He also submitted a bill for his expenses — $190.40 to hire one man with a dog sled, dog team and equipment; all provisions and supplies, including one new pair of snowshoes; and 60 pounds of fish to feed the dogs.

In his report, Lukens suggested numerous upgrades, including the construction of small bridges, the widening of much of the trail, and the rerouting of portions of the trail to avoid areas prone to overflow and steep side-hills.

According to Lukens, the winter route already featured two 12-by-12-foot canvas shelter tents, provided with stoves, between Jean Lake and Moose River. One tent was available near the top of the pass by Upper Jean and Dog Team lakes, followed by a second tent in the wooded moraines northwest of Hideout Hill.

Lukens recommended the creation of “several” log shelters to improve the safety of mail carriers and their dogs. After a homesteader cabin at the junction of the Moose Pass-Sunrise wagon road, the next available shelter for mail carriers in 1923 was a “first-class” 12-by-16-foot log cabin, equipped with a stove, about 4 miles up Quartz Creek from lower Kenai Lake. From there, he said, several good shelter cabins were available on the southern side of the Kenai River until Schooner Bend.

Beyond the bridge, however, reliable shelters (excluding the two tents) were few and far between.

Most of Lukens’ suggested improvements were completed within a year. In February 1924, A.R.C. superintendent Hawley W. Sterling (namesake of the Sterling Highway) announced the shelter upgrades:

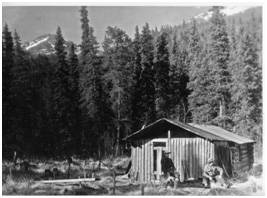

On the western end of Jean Lake, an old prospector’s cabin — which the A.R.C. had been given permission to use — had been braced and chinked, had corrugated iron added to its roof and received a new stove and pipe.

Two new cabins had also been constructed — Middle Cabin near a small stream draining Browse Lake on the flats, and Moose River Cabin at the confluence of the Moose and Kenai rivers.

Each new spruce-log cabin was 14-by-16 feet and covered with a roof of poles, dirt and corrugated iron. Each had one door and two windows, plus a sheet-iron stove. The total cost of building the two new structures and upgrading the cabin at Jean Lake was $750.

Ironically, just one year later the A.R.C. initiated a new project that would eventually eliminate the need for overland winter mail routes altogether — the construction of airports and airstrips across Alaska.

These airports and airstrips quickly began to handle more and more of Alaska’s mail. In 1930, airplanes began landing on the Kenai beach once a month with the mail, and by 1934 an airstrip had been created on the Kenai bluff.

By 1939, more than 100 territorial airports had been built, the A.R.C. had stopped its shelter-cabin maintenance, and the end of the mail-sled era was at hand. The bulk of the mail throughout Alaska was being carried by airplanes, which could arrive every day on airstrips carved next to many rural communities.

A year later, the village of Kenai was on its 13th different postmaster, and changes to the peninsula infrastructure continued apace.

In 1947, as the Kenai Burn charred more than 300,000 acres of the peninsula, construction was well under way on the Sterling Highway, connecting by road nearly every community on the peninsula.

In 1955, The Alaska Sportsman magazine reported that a new steel bridge, located away from the tight river meander at Schooner Bend, would soon be erected and the old bridge torn down.

In 1972, a Kenai National Moose Range inventory of historic and archaeological places assessed the state of the Moose Pass-to-Kenai mail route and determined that “most of the area of the trail burned during the fire in 1947.”

The tent shelters were gone. The shelters cabins became ruins. And the delivery of mail to Kenai became so regular and so commonplace that most people took it for granted unless they had late packages or unexpected fees or the price of postage rose again.