By Clark Fair

For the Peninsula Clarion

AUTHOR’S NOTE: On April 8, 1918, in the roadless village of Kenai, two freshly killed men, covered with sheets, lie in a cabin. Their deaths are the talk of the community.

One of the two men shot the other during a school board election. A third person, currently awaiting arraignment, shot the first killer in a general store shortly after the election ended.

Two village representatives are now on a dogsled, beginning the long, slow cross-country trip to Seward to report the killings to a U.S. deputy marshal. Their version of the story will make headlines and gossip fodder on the Kenai Peninsula, as will other, later versions elsewhere.

So what happened here? And what will happen next?

Peeling back and examining the layers of events is no simple matter. In fact, the unraveling may never be complete. But this is a story worth telling, for it says as much about Kenai a century ago — about Russian influences, about frontier Americans manipulating Native Alaskans, about education and commerce, about law enforcement and the absence of it — as it does about those two dead men.

This, then, is a complex tale of a changing Kenai and of four men — not just the two dead ones — and their perhaps inevitable fatal collision.

It is also a story I would be incapable of telling without the writings and scholarship of others. Before my narration begins, I want to acknowledge some of my sources:

“The Invisible People,” 1991, by Tom Kizzia; a 2014 three-part series about education in Kenai in the 1910s, by Brent Johnson; “The Clenched Fist,” a 1948 memoir by Alice M. Brooks and Willietta E. Kuppler; “Journals of Nineteenth Century Russian Priests to the Tanaina: Cook Inlet, Alaska,” 1974, by Joan B. Townsend; Coleen Mielke’s comprehensive online collection of historical data for Southcentral Alaska; Colleen Kelly of the Resurrection Bay Historical Society; former Kenai National Wildlife Refuge historian Gary Titus, historian Shana Loshbaugh, state archivist Chris Hieb, and many other generous individuals who provided pieces for this jigsaw of events.

THE OPPRESSOR

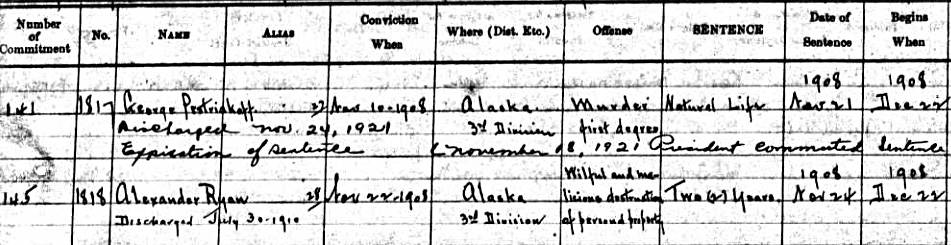

On Dec. 22, 1908, Alexander R. “Paddy” Ryan began a two-year sentence in McNeil Island federal penitentiary in Washington state. The prison logbook listed him as age 43, married, a shade under 5-foot-8, weighing 168 pounds, fair complected, with light blue eyes, and gray hair on a nearly bald head.

Not exactly the standard description of a tyrant, a tormenter, an evil-doer. And yet Alex Ryan had been called all of those things, and more, by the residents of Kenai — a mixture of mostly Alaska Natives and Creoles with Russian ancestry, plus a smattering of white Americans.

Ryan’s prison paperwork said he had been convicted in Alaska’s Third Judicial Division for “willful and malicious destruction of personal property.” The details of that destruction — and the reason for it — are unclear.

The reason he was so widely detested and feared in Kenai, however, is unambiguous.

Alex Ryan was born on the island of Cape Breton in Nova Scotia, Canada, in about 1865. Twenty-one years later, in 1886, he immigrated to the United States. In 1888 he came to the Kenai Peninsula.

His appearance drew the attention of Father Nicholas Mitropolsky, the Russian Orthodox priest for the Kenai parish, who noted that “a white man named Aleksandr Ryan” had arrived in remote and roadless Kenai.

Like much of Alaska at this time, Kenai was home to few legal entanglements. Only two decades free of imperial Russia, the District of Alaska, as it was known then, was a work in progress — still more than two decades from territorial status, about 70 years from statehood.

The U.S. military had had a fleeting presence in Kenai and elsewhere, but Alaska was a distant outpost, ripe for the picking by Americans seeking to exploit the absence of law enforcement.

Historian Joan B. Townsend described it this way:

“Alaska was a frontier, and the United States virtually ignored it. Forces of law and order were remote and unattainable for most villagers, even had they the knowledge and facilities to make use of them. Thus, unscrupulous persons, particularly if they had the backing of a powerful company such as the Alaska Commercial Company and if they were in a position of some power themselves such as storekeeper, could be virtually a law unto themselves, running roughshod over the local populations.”

Thus it was, almost immediately, with Alex Ryan, who became a local storekeeper.

Phil Ames, a student of history and former Kenai lawman, understood the Ryan type. Speaking at a 1974 history conference, Ames amplified Townsend’s points:

“Typically the storekeeper had the key to everything — the post office, the mail sacks, the kerosene barrels, the groceries, the blankets, the clothing. He had an economic hold you wouldn’t believe today. He had no competition, none at all in any field he wanted to engage in. And if he was a bully — and Ryan obviously was — there was really nobody could stop him.

“He probably had 90 percent of the people owing (his store) most of what they were going to make for the coming year … and this was one reason he could get away with (his) high-handed behavior. People were simply afraid to buck him because they would lose their credit at the company store.

“If the storekeeper was a man of conscience, the village was all right. But if you got a Ryan, heaven help you. Nobody else could.”

Alex Ryan became a naturalized U.S. citizen in about 1889. Somehow, by at least the early 1890s, he had also managed to become a U.S. special deputy marshal for the Cook Inlet region. On Feb. 18, 1891, in Knik, he, along with two other men, hanged a Copper River Native man accused of murder.

When complaints about the execution were filed, Justice of the Peace James Wilson sided with Ryan. He issued a certificate stating that Ryan and the other men had “acted in compliance with the rules of the American government when they hanged a Copper River savage.”

The story of the hanging — and its official sanction — was soon well known in Kenai, as was Ryan’s brutality.

AN ATTEMPTED SOLUTION

Ryan, who began running the Alaska Commercial Company’s Kenai store around this time, routinely had his way with the people of the village — with one exception. When Father Alexander Yaroshevich took over the Kenai parish in 1893, he became one of the only men willing to confront Ryan. For this willingness, Yaroshevich and his parishioners paid dearly.

Ryan and his drunken friends once aimed their pistols at the old church and blazed away until they had shot down the cross from the top. With regularity, Ryan brandished his pistol at villagers and threatened them with more hangings. Angry at Yaroshevich’s resistance, he refused to sell the priest food from the town’s only store.

Yaroshevich preached the value of sobriety and the evils of alcohol. Ryan, on the other hand, illegally brewed vodka in the back of his store and supplied it to the Natives.

The priest complained. He sought legal recourse. “All measures of the government and laws of the United States are trampled down at Kenai by such scoundrels as Ryan,” he wrote. But the nearest Justice of the Peace at the time was stationed in Kodiak, so Ryan’s actions went unpunished.

Perhaps emboldened by this lack of consequences, Ryan continued acting out.