AUTHOR’S NOTE: In the first part of this story, William Dempsey, murderer of two Alaskans in 1919, escaped from prison in Washington in 1940, alarming the man who had convicted him. Part One also introduced Dempsey’s first victim, an Anchorage prostitute named Marie Lavor. Part Two introduces the second victim and the trial judge.

The Marshal

The assignment received in Seward by Deputy U.S. Marshal Isaac Evans in late August 1919 must have seemed fairly routine: Be on the lookout for a young man suspected in the disappearance of Marie (or Margaret) Lavor in Anchorage.

The suspect, William Dempsey, possibly traveling under an alias, was described as thin, about 5-foot-7 and 150 pounds, with brown hair and gray eyes. Anchorage authorities believed Dempsey was planning to sail from Seward and flee to the States.

Marshal Evans had already spread the word. Early on Sept.1, he had walked into the office of the Alaska Steamship Company and provided the agent there with a detailed description of Dempsey.

Then, just after nine o’clock, Evans spotted a likely subject. The man, calling himself William Cummings but fitting the description of William Dempsey, walked out of the railroad administration building, where he had attempted to cash a recent paycheck. Evans detained Cummings, performed a cursory search of his person, and then walked him over to the nearby marshal’s office for further questioning.

Before entering the office, Dempsey dropped a bundle of clothing and other belongings outside on the ground. Inside the office, Evans required only a few minutes to assure himself that he had apprehended the right man. He decided to lock up the suspect in Seward’s federal jail and hold him there until a marshal arrived from Anchorage.

But here Evans’s many years of experience let him down. And his error became his undoing.

Fifty-five-year-old Isaac Evans had been born in Pittsburgh to Welsh-born parents in July 1864. When Isaac was still young, the family moved to Tennessee, where his father became a coal miner. Isaac himself later headed for the West Coast, eventually settling in what was then the fast-growing village of Tacoma, Wash. Evans would spend most of the rest of his life in either Tacoma or various places in Alaska.

During much of his tenure in Tacoma, he worked either in the sheriff’s office or as a police detective.

Evans first traveled to Alaska in February 1898. He entered the customs service at Wrangell, working the international border during the gold rush to the Cassiar district. He later became a customs inspector along the Stikine River, and he was in attendance at Lake Bennett on July 6, 1899, when the golden spike was driven to commemorate the completion of the White Pass & Yukon railroad route.

The following year, in October, he married Wisconsin native Elvira Cushin in Tacoma. She traveled with him to many of his duty stations in Alaska.

In 1901, he became a U.S. deputy marshal in Teller, near Nome. He remained there until 1907, when he was transferred to Candle, on the Kiwalik River. While in Teller, he did some prospecting and became one of the first men to locate a tin deposit in Alaska.

Evans fell ill in the fall of 1908 and returned to Tacoma to recuperate. By 1910, with his health restored, he was working on an area gold-mining operation. Soon, though, he returned to law enforcement and then to Alaska. On Nov. 23, 1911, he and Elvira sailed out of Seattle to Seward, where Isaac had accepted a deputy marshal job.

Over the course of his life, Evans was a member of the Elks Lodge in Tacoma, a secretary for the Pioneers of Seward, a senior warden of the Masonic Lodge in Seward, and a member of Alaska Consistory No. 1 in Juneau. He was well-liked in Seward during his time as marshal.

He had been on the job for nearly eight full years when the call came in to watch out for William Dempsey, and when he made his fatal mistake.

The Judge

Charles Bunnell worked as a public-school teacher in Kodiak and Valdez in the early 1900s. Simultaneously, via correspondence courses, he completed a master’s degree in 1902 and a law degree in 1905, both from Bucknell University (in Pennsylvania). He passed the Alaska bar exam in November 1908, and began his law career in Valdez that same month.

In 1914, Pres. Woodrow Wilson appointed Bunnell to be the judge of the Federal District Court for the Third and Fourth divisions of the Alaska Territory. Bunnell held court sessions primarily in Fairbanks.

In the fall of 1919, however, he found himself traveling more than usual because he needed to help cover for another district judge who was suffering from a long-term illness. Consequently, Bunnell was scheduled to hear cases in Anchorage, Cordova, Seward and Valdez, as well as in the Interior.

This schedule required him to be the judge during the two murder trials of William Dempsey and, much to his surprise and dismay, would connect him to Dempsey, and to a trio of women who could be called Dempsey’s “prison groupies,” for the next two decades.

Charles Ernest Bunnell was born in January 1878 in Dimock, Penn. At the age of 22, he earned a bachelor’s degree from Bucknell and shortly thereafter began teaching on Wood (now Woody) Island, across a channel from Kodiak Island.

A year later, back in Pennsylvania, he married another teacher, Mary Ann Kline. He brought his bride to Alaska and both continued their teaching careers, moving to Valdez in 1903. After completing his law degree, he worked as a bank cashier and began studying for the bar exam under the tutelage of Valdez attorney Edmund Smith, with whom Bunnell later established a law firm.

Meanwhile, Bunnell remained busy elsewhere. He became a school board member and the president of the Valdez Chamber of Commerce.

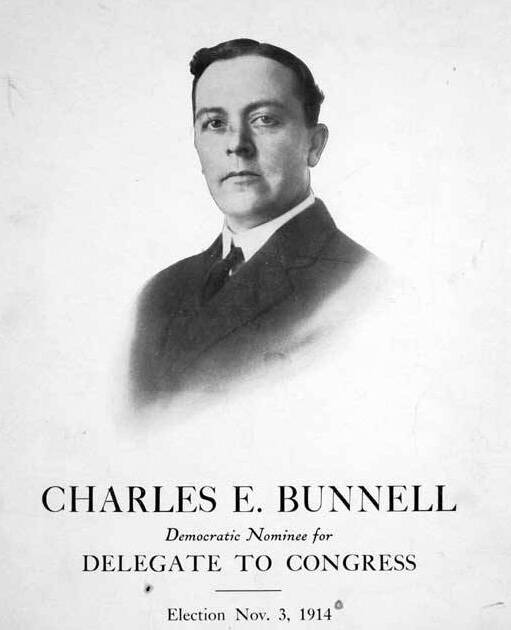

The Bunnells’ daughter, Jean, was born in 1909, but even that event failed to slow the career march and the numerous endeavors in which Charles Bunnell immersed himself: In 1912, he was elected Territorial committeeman for the Third Division. In 1914, he was nominated by the Democrat Party to be a delegate to Congress, and he became a federal judge.

Then, in late 1921, Bunnell was elected by the Board of Trustees to become the first president of the Alaska Agricultural College and School of Mines — predecessor of the University of Alaska — in Fairbanks.

During all this time, he maintained a very busy work schedule. William R. Cashen, Bunnell’s biographer, said the college president typically worked seven days a week; consequently, wrote Cashen, “his home life became of secondary importance, and his marriage, which had been less than harmonious for several years, finally collapsed.”

In 1929, Bunnell’s wife traveled to her family home in Pennsylvania to care for her ailing father. She did not return to Alaska. The Bunnells never divorced, but they also never reconciled. Their separation remained permanent, and neither ever remarried.

Mary Ann Bunnell’s departure from Alaska marked the 10th year since the former judge had tried the two Dempsey murder cases and the third year since William Dempsey had begun corresponding, from prison, directly with the man who had sentenced him to die.