Ben Swesey: More to the story — Part 4

Published 1:30 am Thursday, February 19, 2026

AUTHOR’S NOTE: Seven years after his friend William Weaver nearly drowned in Kenai Lake while returning from guiding a wealthy East Coast hunter in the Kenai Mountains, Seward’s Benjamin Swesey guided a pair of New Yorkers into the mountains for what would prove to be his final guiding job.

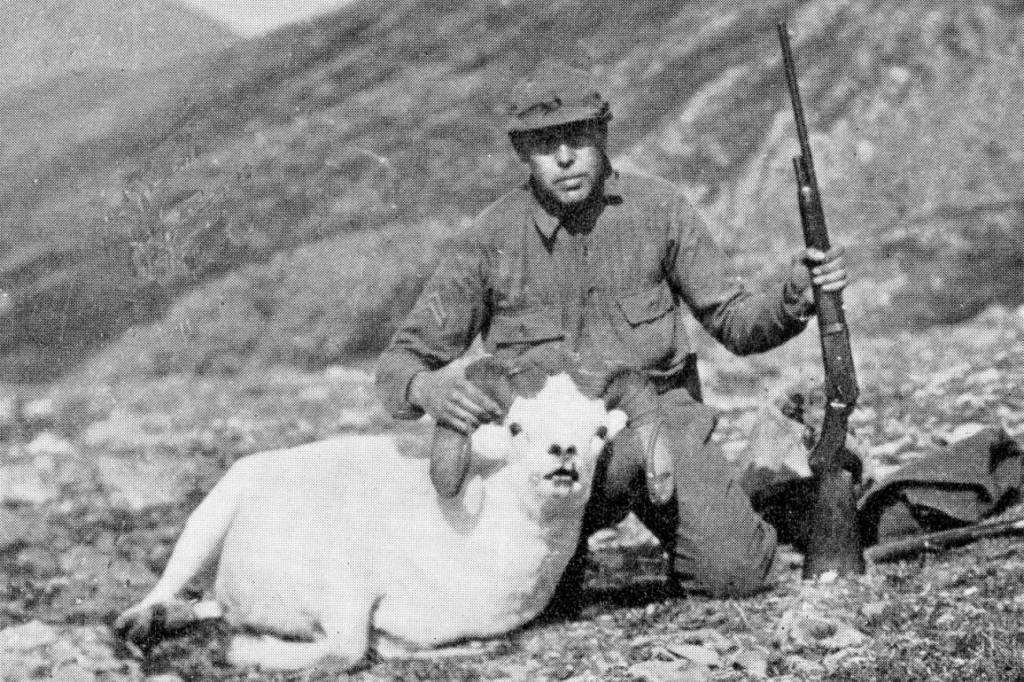

Although no one knew it at the time, Seward’s Ben Swesey served as a hunting guide in the Kenai Mountains for the final time in August and September of 1917.

On that occasion, which involved two wealthy New York clients, Swesey worked with fellow Seward-area guide Andy Simons and two local packers, Tom Finnegan and Walter Lodge. The clients were John P. Holman and Malcolm S. Mackay, who sought to fill their limit of three Dall sheep apiece.

The hunt, near the headwaters of the Killey River, was planned for about four weeks. When the two sportsmen arrived in Seward in mid-August, the guides took them shopping for provisions and supplies. Before they left town, they had purchased more than 800 pounds’ worth—so much that the guides and packers built a log cache in which to store much of the foodstuffs along the south shore of Skilak Lake.

During their return from the hunt, all six men, after battling a drenching, multi-day rainstorm, reached Seward in mid-September, toting six sheep heads and a black bear hide. Swesey, who had guided Holman while Simons guided Mackay, had duly impressed his client enough to merit several lines of praise in the hunting memoir Holman penned in 1933.

Holman spoke of Swesey’s “traits of character that endeared him to us all.” He called Swesey “calm in temperament and very resourceful,” adding that Swesey “looked on life with the true philosophical mind and took a quiet enjoyment in his surroundings. His droll chuckle over some amusing incident along the way bespoke a depth of dry and genuine humor.

“He was wonderfully alert in all his actions,” Holman continued, “and possessed a patience that was truly marvelous. He loved the wild creatures and the environment in which they lived. His greatest joy was to wander away from camp during the long northern evenings and search the mountain slopes for bear….”

Mackay, in his own 1925 hunting memoir, remarked that Swesey was “really a wonderful character, patient, kind, humorous, wise and tough as rawhide, a man to tie to in a tight place, a man to enjoy in the glow of the camp fire.”

Both sportsmen-authors paid particular attention to Swesey because they had been informed that, only weeks after they had departed for the East Coast back in 1917, Swesey, along with fellow outdoorsman William Weaver, had gone missing and was presumed dead.

Interestingly, Holman’s comments on the disappearance also indicated that there might have been more to the narrative being peddled to the public at the time. Holman claimed that Swesey had drowned “in fulfilling a dangerous duty for the sheriff of Seward.”

About 30 pages later, he returned to the same topic: “[Swesey] undertook to run down some boot-leggers who were supposed to be in hiding along the bleak and barren coast to the westward.”

If running down some bootleggers was the true aim of Swesey and Weaver’s exit from Resurrection Bay, it must have been a secret mission. No hint of this task appeared in newspapers in 1917 or 1918.

Hunting trips

Most reports of Swesey and Weaver’s trip out of Seward indicate a departure on about Oct. 15 in Ben Swesey’s dory, equipped with a small Evinrude outboard. Their purported goal was a two-week hunting trip in Aialik Bay, which they planned to reach by traveling around the lower western edge of Resurrection Bay.

Holman’s memoir added this: “They used the same outboard that had played us such tricks on Kenai Lake.” Holman had described those “tricks” earlier in the same chapter:

After descending from the mountains, motoring across Skilak Lake and lining a heavily laden boat up the Kenai River canyon and the upper river toward Kenai Lake, Holman, Mackay and their guides and packers set out to cruise up the lake to meet the train bound for Seward. Holman estimated the boat trip would take four to five hours.

They began near the mouth of Cooper Creek in the early morning and soon reached smooth, open waters of the lake, but after only a mile or two, the conditions began to change. Holman noted an increasing cloudiness and a strengthening wind. Before long, he said, the skies were completely overcast.

“We chugged along, shipping seas, getting drenched by spray, but rather enjoying the sudden change in the weather,” Holman wrote, “until a tell-tale miss in the even song of the motor gave a new trend of thought for our imagination to feed upon. As if in answer to our questioning thoughts, it suddenly did as we expected—stopped as dead as a piece of iron.”

The men quickly manned the oars, but the craft, packed with gear, hunting trophies and six adults, responded sluggishly. The rolling waves began cresting with white caps, as Swesey, in the stern, kept “spinning the flywheel of the motor with patient persistence.” Two men to each oar, they pulled for all they were worth to keep the boat moving forward.

“The motor,” said Holman, “seemed to have realized at last that Ben would have kept on spinning it forever and so responded with a good grace to the inevitable just in time to overcome the pressure of the hosts arrayed against us.” They steered into the lee of what was probably Porcupine Island and attempted to wait out the storm.

At about 9 p.m., a man piloting a freight boat down the lake discovered them and offered to tow them the rest of the way, eliminating the need to trust Swesey’s outboard.

It is unclear how Holman knew—or whether he merely assumed—that Swesey and Weaver had used the same boat motor on their trip to Aialik Bay, but if he was correct, it may lend credence to the belief held at that time that Weaver and Swesey had drowned in heavy seas.

What is more certain is that no one considered the two men missing or in danger until at least a week had passed. Both men had proven themselves adept at handling difficult situations in the outdoors. Swesey had faced down charging bears. Weaver, in 1910, had survived a near-drowning on Kenai Lake. However, both of them certainly realized that misfortune can sometimes defeat even the most careful adventurers.

TO BE CONTINUED….